Mount Rainier: Takhoma's Many Histories

The Place

Location: Mount Rainier National Park, Washington

Subjects: Mount Rainier; mountaineering; national park scenery

Time: 1870 - 1900

Mount Rainier: Takhoma’s Many Histories

by Blake Moore

Mount Rainier stands 14,410 feet above sea level and is the most dominant feature in Washington. It’s the tallest volcano in the lower 48, covered by more than twenty glaciers, surrounded by forests and the natural beauty of the PNW. The mountain is within Mount Rainier National Park, which protects over 230,000 acres of land. To most visitors, it’s a place of beauty and challenge. Though long before it became a national park, it was a sacred mountain known by a different name. Before it was called Rainier, Indigenous peoples of the region knew the mountain as Takhoma, Tacobet, or Tahoma. The Puyallup, Nisqually, Cowlitz, Muckleshoot, and Yakama communities used these names, often meaning “the source of nourishment” or “the mountain that was God.”

For thousands of years, they traveled through the area to fish, gather berries, and trade. The glaciers that come off the mountain fed into the rivers that sustained salmon and connected their villages. To them the mountain was alive, not just a landmark, and its stories were part of how the people of this land understood the world.

The name Mount Rainier came from British explorer George Vancouver in 1792. He renamed it after a friend, Rear Admiral Peter Rainier. Settlers and explorers adopted that name and ignored the older ones that had existed for generations. Through the 1800s, settlers moved into the region and Indigenous families were forced from their lands. When Mount Rainier National Park was created in 1899, the government described it as untouched wilderness. This however was not the case. The land had been cared for and managed by Indigenous people through burning and selective harvesting. The new park system celebrated preservation while erasing the people who had shaped the landscape.1

One of the most important moments in the mountain’s later history came in 1870. Hazard Stevens and Philemon Van Trump made what was considered the first recorded climb to the summit. They wrote about it in Overland Monthly as “The Ascent of Takhoma.” Their story described the mountain as both dangerous and holy. They saw the climb as a test of strength and exploration. But even they knew Indigenous guides who knew the mountain well were the reason for their survival. Their story helped make Mount Rainier a national symbol of adventure and discovery.

After the climb, the mountain became a focus of early tourism. Roads and lodges were built and with that came thousands of visitors every year to hike, camp, and attempt to summit the Mountain. Artists and photographers made the mountain famous across the country. Paintings and postcards turned Rainier into an image of the Pacific Northwest itself. But while its beauty was being celebrated, the Indigenous history of the mountain was mostly being left behind.

The Nisqually people have one of the oldest connections to the mountain they call Tahoma. Their homeland followed along the Nisqually River. It went from the lands near Olympia to the glacier that runs off the mountain’s side. Each summer their families went up the valley to hunt, pick berries, and gather cedar bark. To them, Tahoma was alive and a spirit that shaped the world while giving life through its snow and rivers. One story tells of a great flood that covered the earth. In it, only a woman and her dog surviving by climbing to the top of Rainier. When the waters dropped, they followed the rivers home and repopulated the land. Another story says the mountain was once a woman who lived with the people before she rose into the sky and became the peak itself. She left behind a white blanket of snow as a gift that kept the land fertile. These stories taught respect and warned against treating the land wrongly.

When Mount Rainier National Park was created in 1899, the Nisqually were shut out of the mountain and the surrounding area. The government called it wilderness, even though they were taking care of these forests for hundreds of years. After the park’s creation, gatherings and ceremony were banned and Native families were turned away. In recent years, the Nisqually Tribe has begun working with the National Park Service to restore those connections and protect sacred areas. Tribal educators now share the stories of Tahoma and spread its rightful history.

Understanding Mount Rainier today means looking at the full story. The mountain’s beauty is only one part of it. Every aspect of the mountain and area, from the trails, meadows, and glaciers carry the history of people who once lived here. To really know Takhoma is to see it as a sacred mountain that shaped the PNW we know today.

Works Cited

-

Nisqually Indian Tribe. “Heritage.” Official Site of the Nisqually Indian Tribe, www.nisqually-nsn.gov/index.php/heritage/. Accessed 10 Nov. 2025.

-

Plateau Peoples’ Web Portal. “Tacobet: Sacred Mountain.” Washington State University Libraries, https://plateauportal.libraries.wsu.edu. Accessed 10 Nov. 2025.

-

Stevens, Hazard, and Philemon B. Van Trump. “The Ascent of Takhoma.” Overland Monthly, 1876, https://www.mountaineers.org/blog/the-ascent-of-takhoma-by-hazard-stevensand-pb-van-trump. Accessed 10 Nov. 2025.

-

Meany, Edmond S. Mount Rainier: A Record of Exploration. Macmillan, 1916. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/mountrainierreco00meanuoft. Accessed 10 Nov. 2025. ↩

Primary Sources

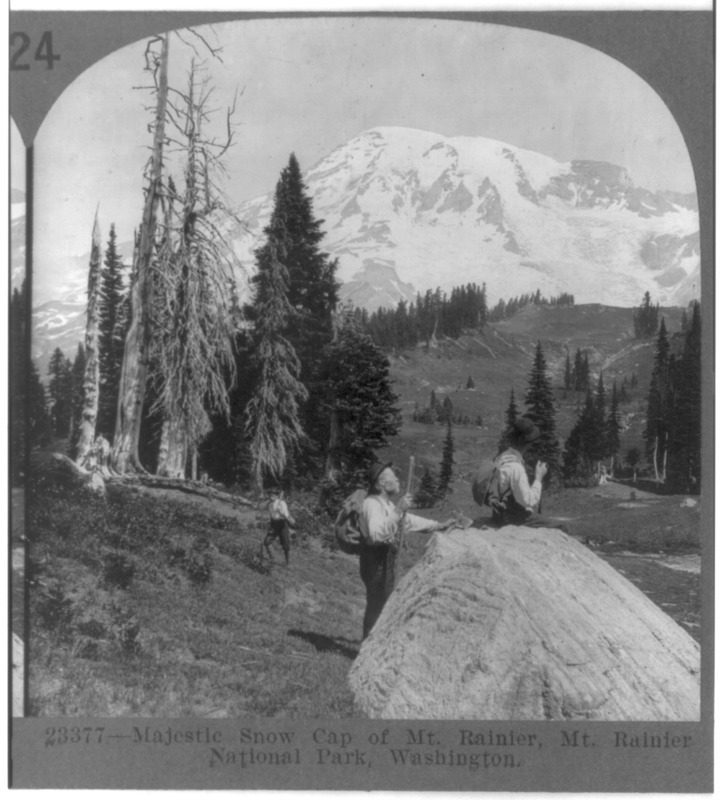

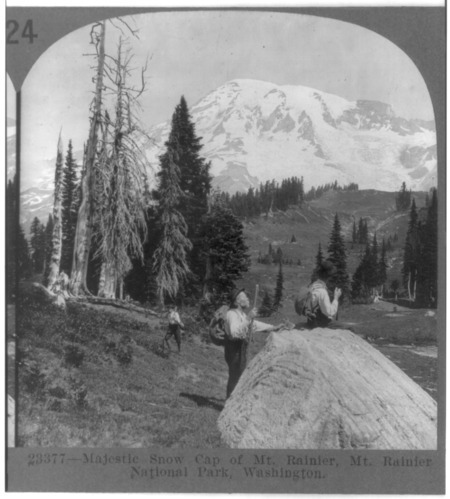

Majestic snow cap of Mt Rainier Mt Rainier National Park Washington

This stereograph represents early twentieth century mountain photography and the growing popularity of mountaineering in Washington. It was distributed internationally by the Keystone View Company. It shows that Mount Rainier's image circulated to promote American natural beauty.

Art as in Mount Heaven Mount Rainer

This image showcases the true beauty of Mount Rainer and the agriculture surrounding it. This high-resolution photo shows the quite art that nature can have when left untouched. The photograph can be seen as a visual comparison to other historic photos of Mount Rainier, showing the environmental change is has seen.