Part Three: The Higher Positions (Excepting Thumb Position)

Higher Positions in General

The construction of our hand allows us a large stretch between the thumb and the first finger. This makes it possible to move the first finger higher than fourth position, while the thumb can go no further up. The positions we can get to in this way are called “higher positions” and can be described as follows:

[“Der erste Finger liegt auf f, b, es, as” = “The first finger touches F, B-flat, E-flat, and A-flat”] [“Der erste Finger liegt auf fis, h, e, a” = “The first finger touches F-sharp, B, E, and A”] [Der erste Finger liegt auf g, c, f, b” = “The first finger touches G, C, F, and B”] [“Der erste Finger liegt auf gis, cis, fis, h” = “The first finger touches G-sharp, C-sharp, F-sharp, and B”] [Der erste Finger liegt auf a, d, g, c” = “The first finger touches A, D, g, and C”]

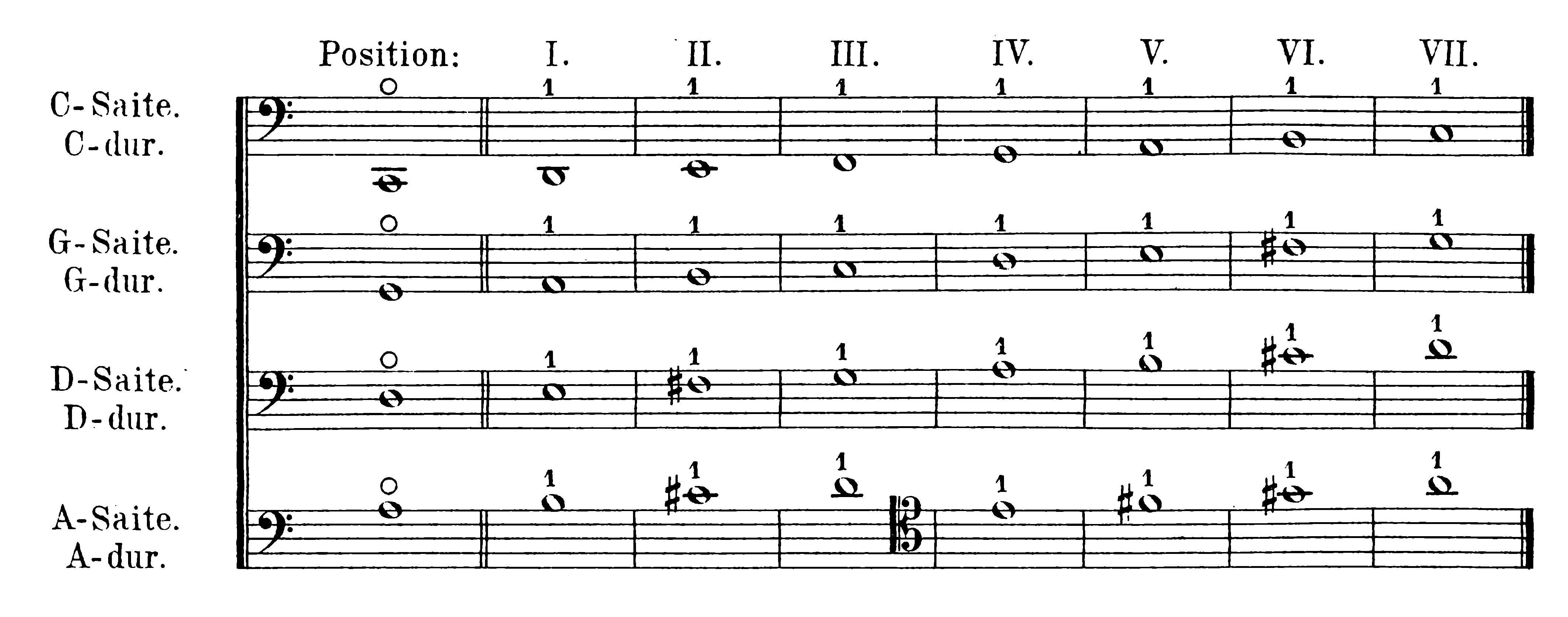

The player will have noticed that the numbered positions correspond to those of the major scale of the open string. Therefore, the first finger is always on a scale-specific interval in the positions with whole numbers.

[“C-Saite” = “C-string”] [“C-dur” = “C major”] [“G-Saite” = G-string”] [“G-dur” = “G major”] [“D-Saite” = “D-string”] [“D-dur” = “D major”] [“A-Saite” = “A major”]

The half-steps between the scale degrees (tonic and second, second and third, fourth and fifth, fifth and sixth, and sixth and seventh) therefore correspond to the respective half-positions: half, 1 ½, 3 ½, 4 ½, 5 ½.

The higher positions differ significantly from those discussed in the first two sections, i.e.:

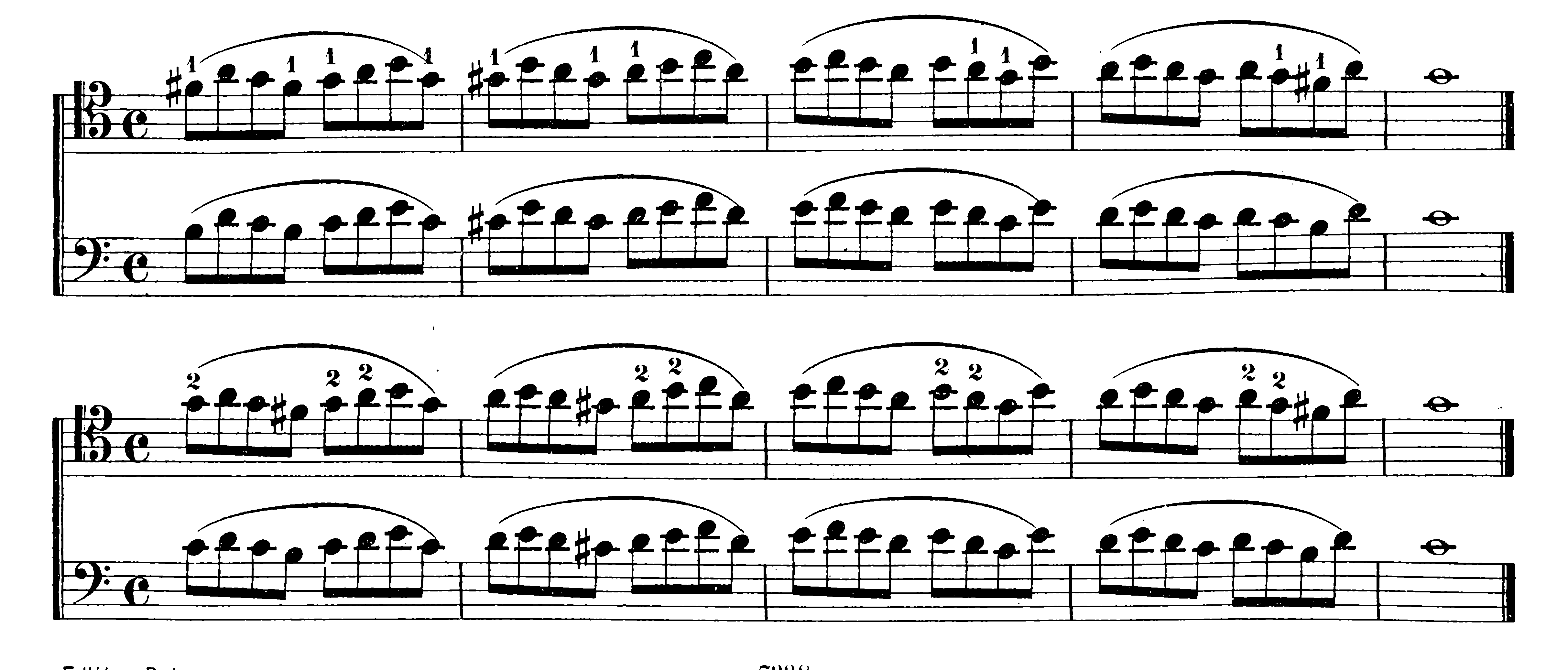

1) Distancing the first finger from the thumb causes the hand to bend to the left. As a result, the fingers also move away from the string to the left. This gives the whole hand a different shaping over the strings. This mostly affects the fourth finger, which suffers the greatest deviation from the thumb and is bent so far to the left of the string that it can no longer touch it. This is why we do not use the fourth finger on pitches higher than G-sharp or A-flat on the A-string, or on corresponding pitches on the other strings. The player therefore can only use three of the fingers in the higher positions.

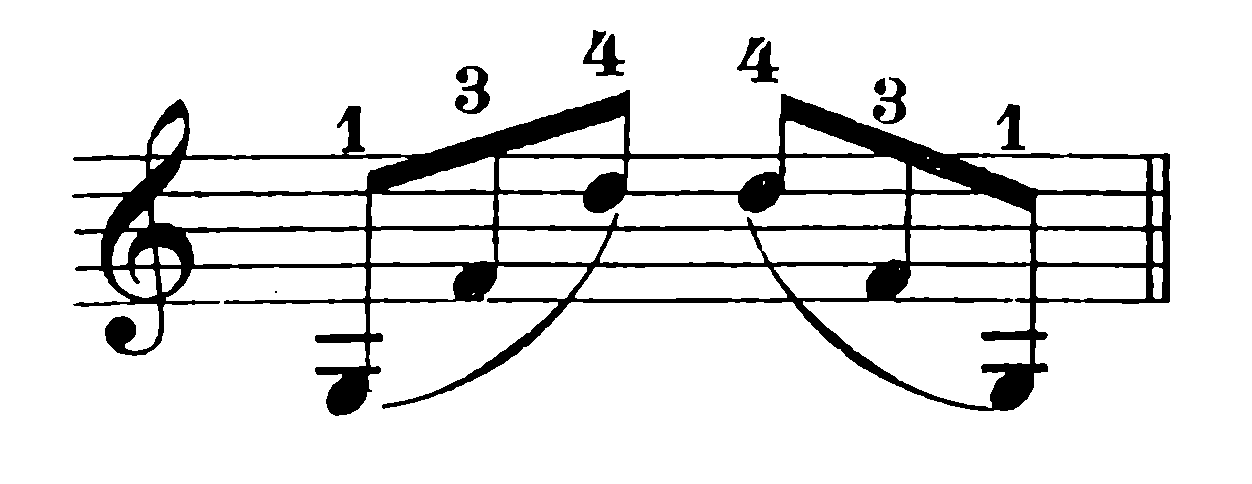

Note: This rule regarding the fourth finger only really applies on the A-string. If the first finger is playing a G in seventh position on the G-string, the fourth finger can play a D in seventh position on the A-string. This is because, even when bent to the left, it can easily touch the A-string. The following fingering is therefore easy to play with the fourth finger:

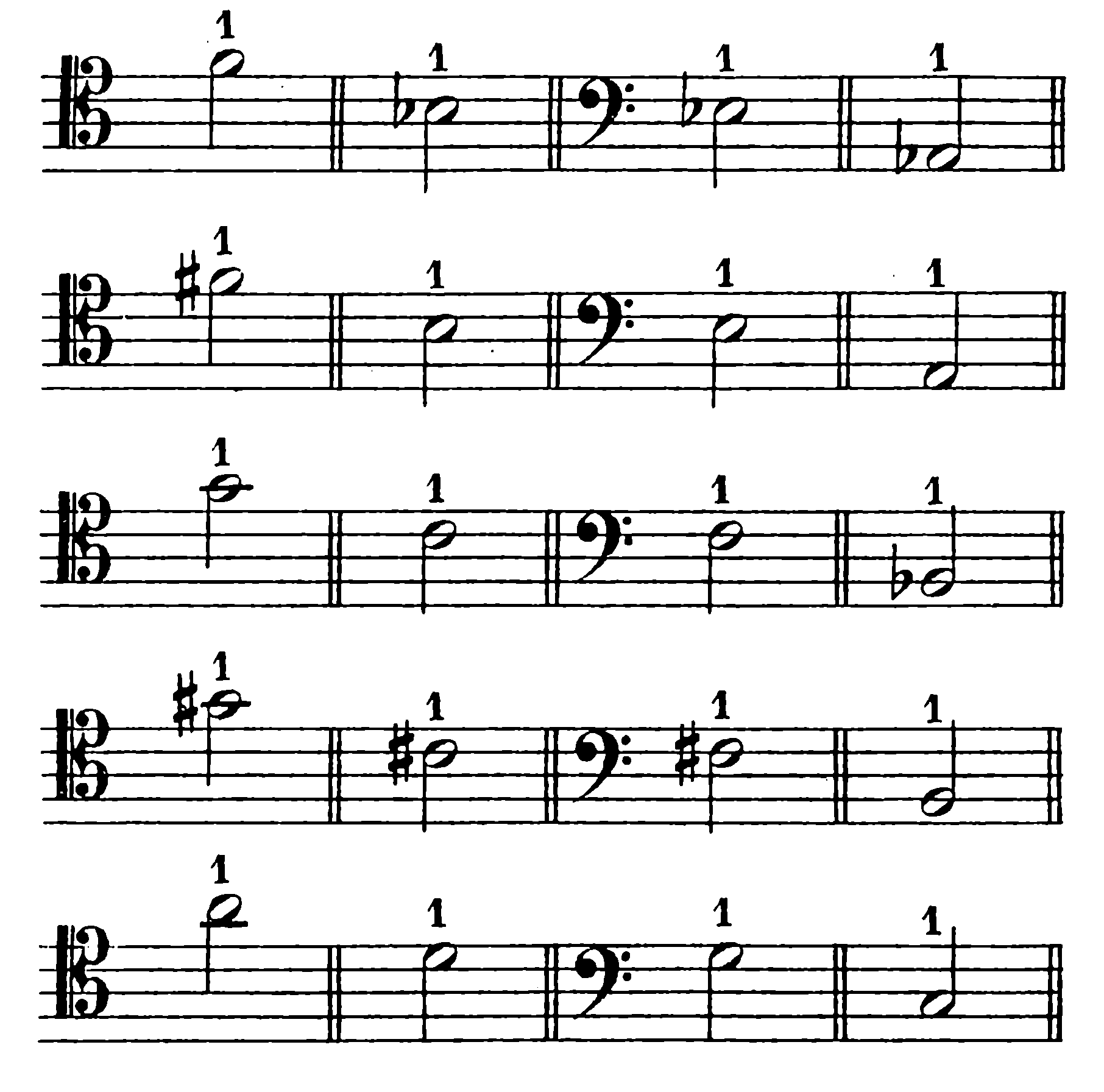

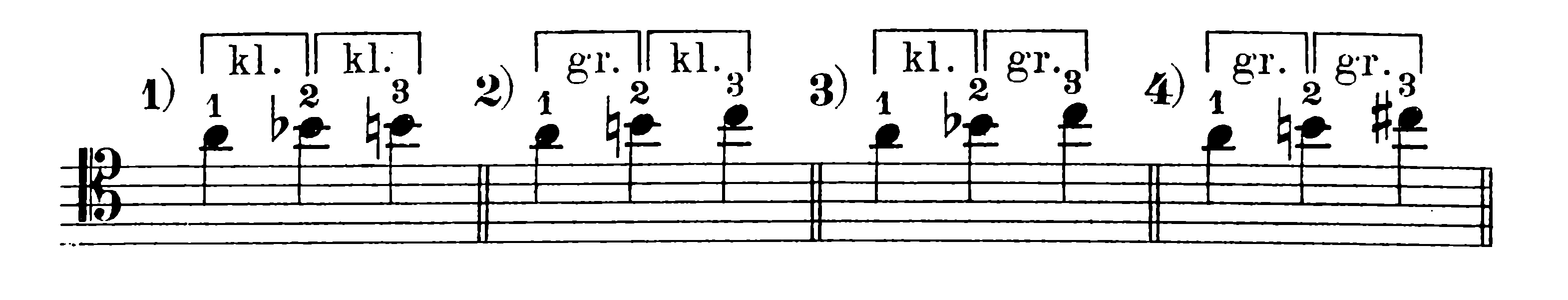

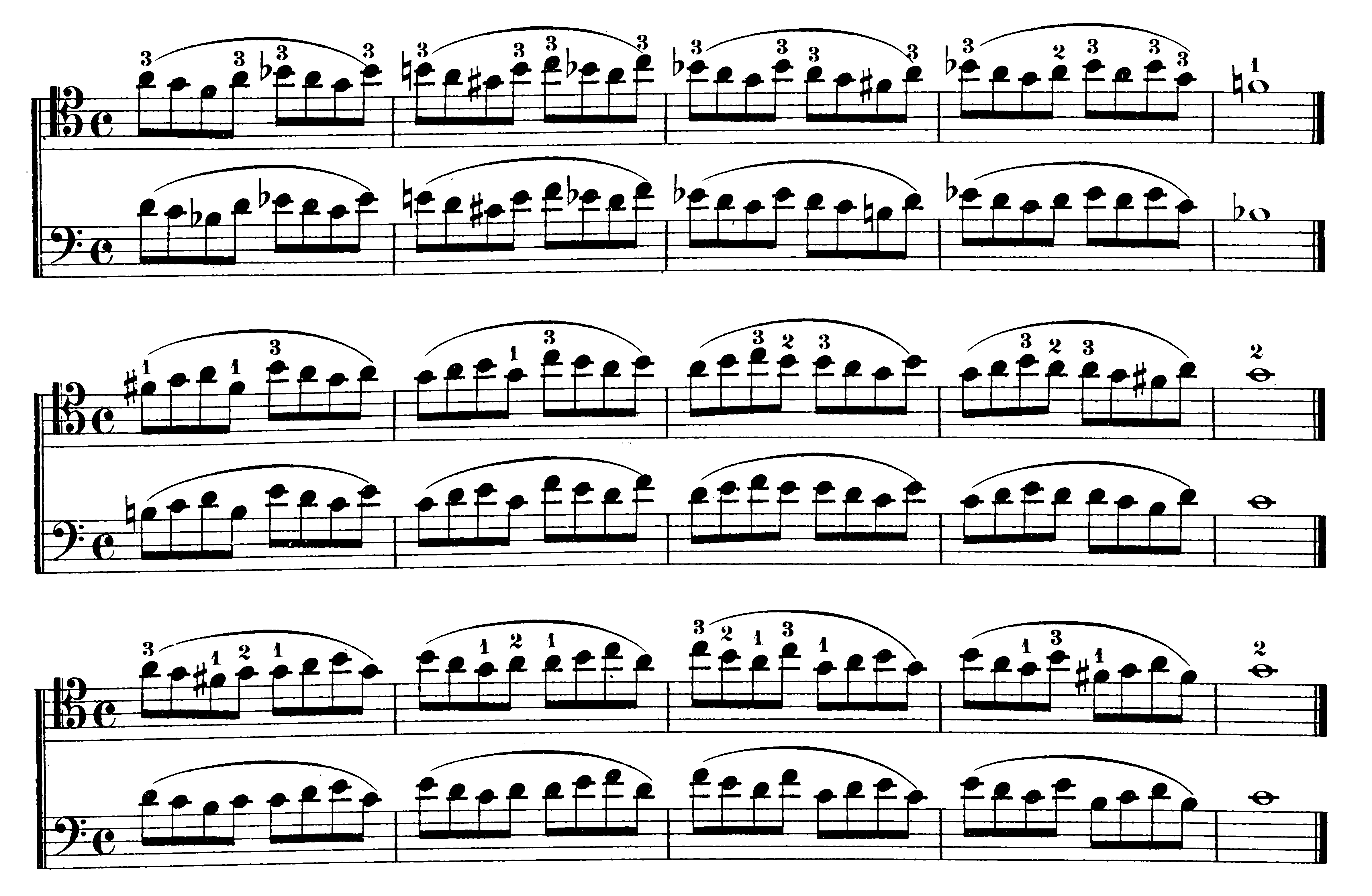

2) The distances between the fingers are so much smaller in higher positions that an extension of up to a whole step is possible between the second and third fingers. In this way, more extensions are possible in higher positions. We can play a whole step between the first and second fingers and between the second and third fingers. Consequently, you get four fingerings: (1) a half step between 1 and 2 and another half step between 2 and 3, (2) a whole step between 1 and 2 and a half step between 2 and 3, (3) a half step between 1 and 2 and a whole step between 2 and 3, and (4) a whole step between 1 and 2 and another whole step between 2 and 3. These fingerings are shown on the A-string in seventh position:

[“kl.” = “closed position”] [“gr.” = “extended position”]

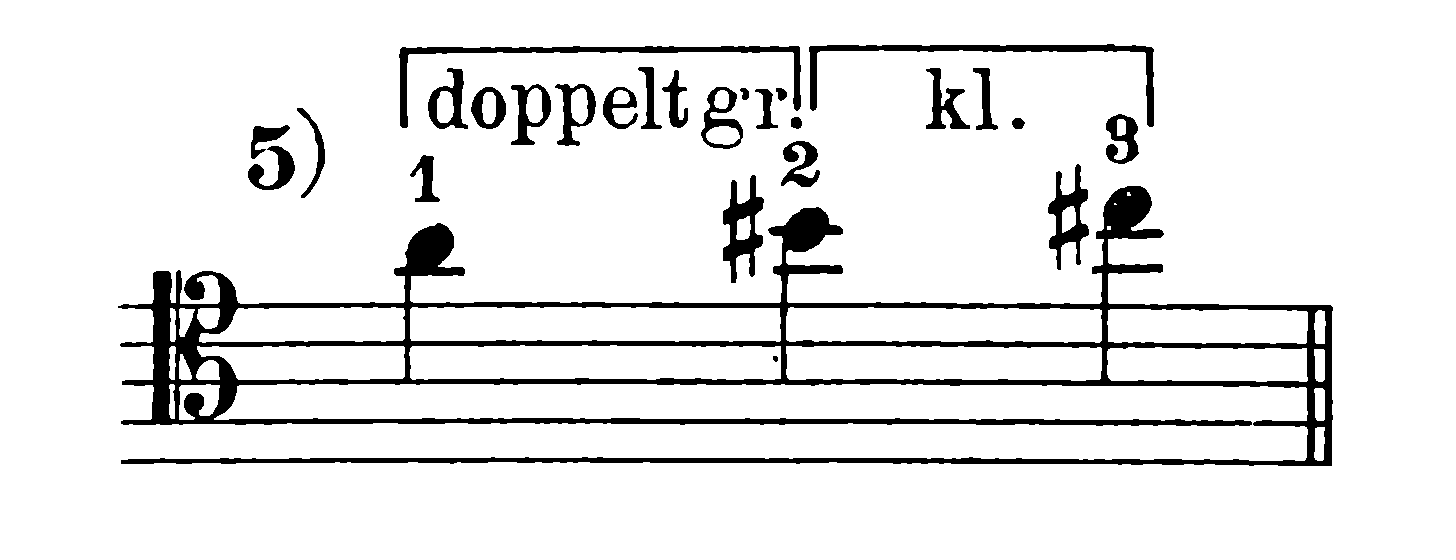

There is a fifth scenario, where there is a stretch of one and a half steps between the first and second fingers, which is easily reached. In this case, however, the third finger would be no more than a half-step away from the second finger, since the stretch between the first and third fingers can never be larger than a major third:

[“doppelt gr.” = “double extension”] [“kl.” = “closed position”]

3) The thumb, unlike in previous positions, is no longer opposite the first and second fingers. This situation is hard to regulate in higher positions because it can vary depending on hand size and thumb length. The thumb, which in fourth position partly encircles the neck of the cello, usually moves more to the left when the hand goes into higher positions. In seventh position, therefore, the tip of the thumb touches the point where the fingerboard meets the neck of the cello. As in fourth position, the hand always rests on the upper bout of the cello, thereby giving necessary support to the position.

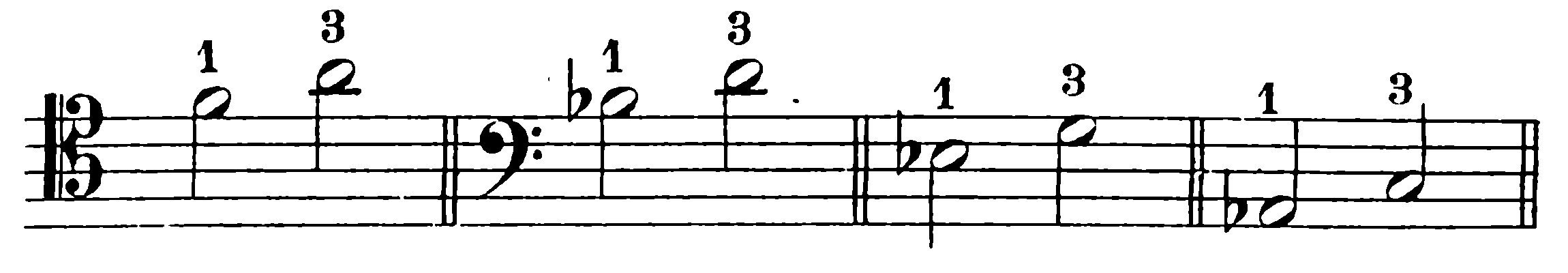

4 ½ position has already been discussed in the previous section as part of fourth position, but it is also sometimes used as an independent position with the fingering 1-2-3 for the interval of a major third, since otherwise the fourth finger would be on A, D, G, C.

The five fingerings discussed appear in 4 ½ position as follows:

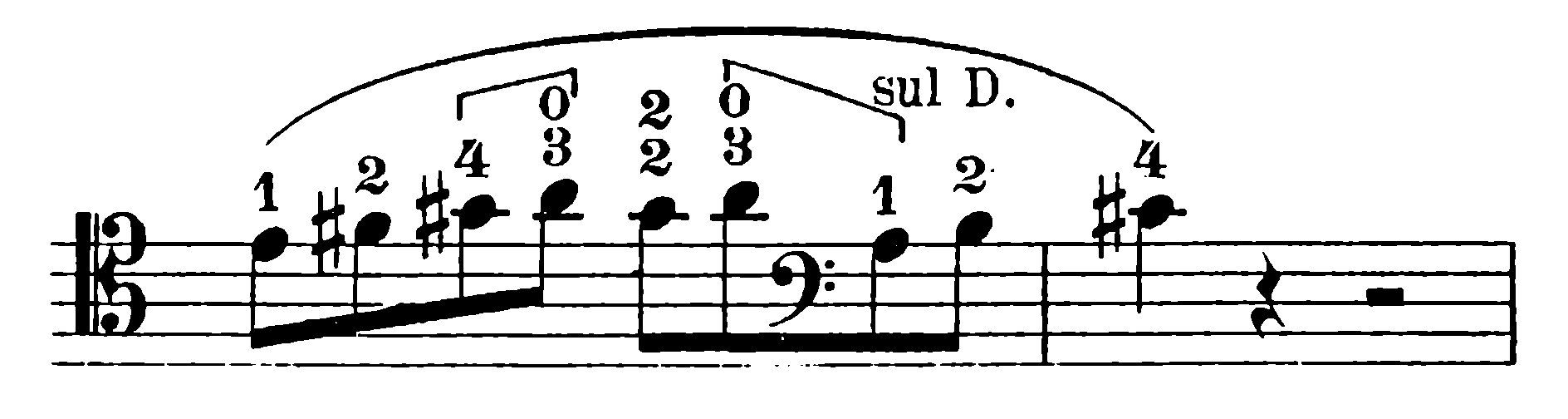

Note: the tones marked “NB” (A, D, G, C) are reached here for the first time. They are at the exact halfway point of each string, and also sound when the finger touches the string lightly at the relevant point. These so-called “harmonic tones” will be discussed in Part Two. Harmonics (marked “0”) are easy to play, even if the finger does not hit the spot exactly. They also continue to sound for a short time after the finger is lifted. This makes it easier to move into a new position from one of the harmonics, as in the following figure:

If the A is lightly touched with the third finger, it sounds absolutely pure, even if the finger has not touched it exactly. (This can be easily confirmed by pressing the finger down.) At the shift to the lower A on the D-string, it is sufficient to lift the third finger and place the first on the A, because the harmonic still sounds after the finger comes off the string.

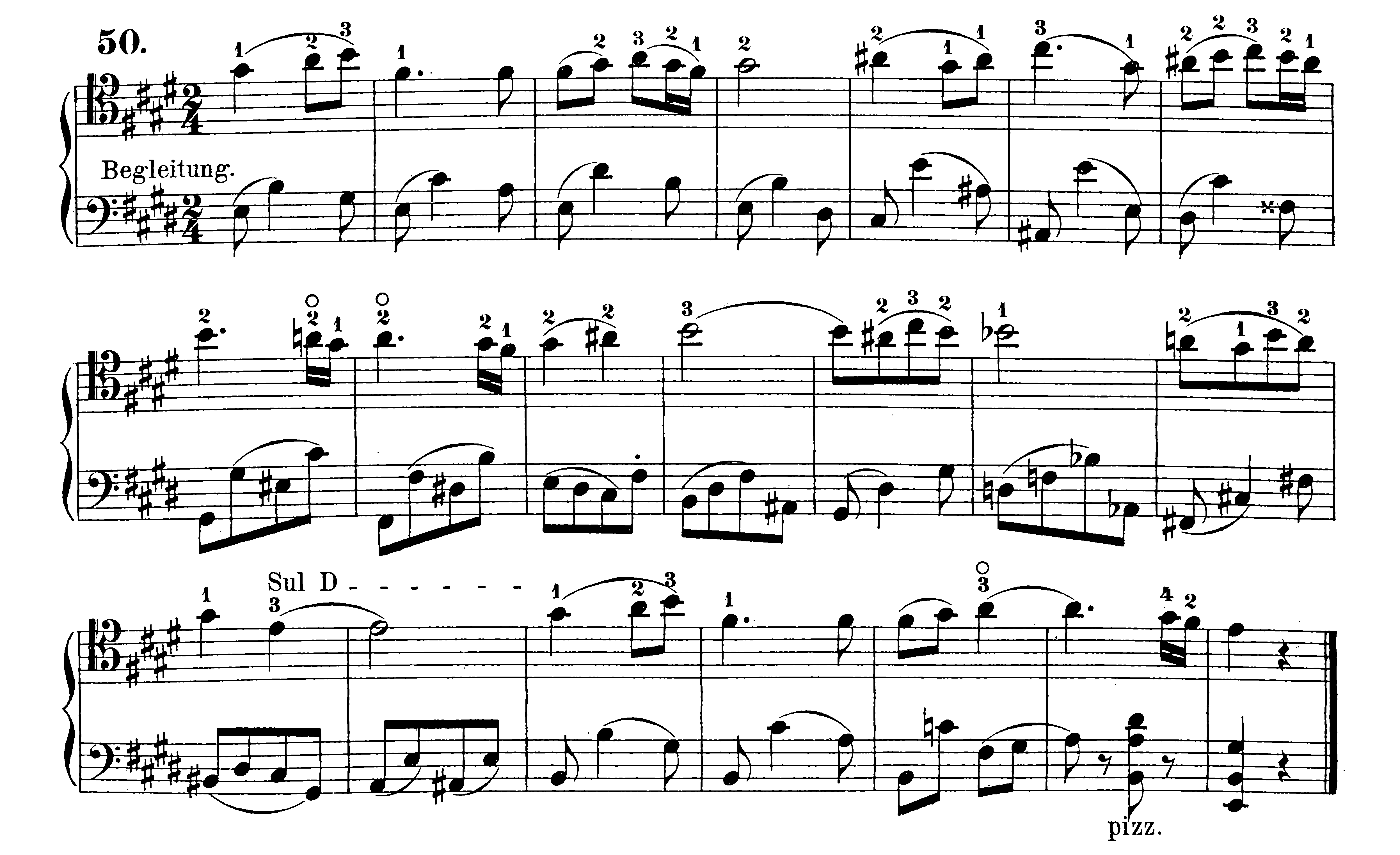

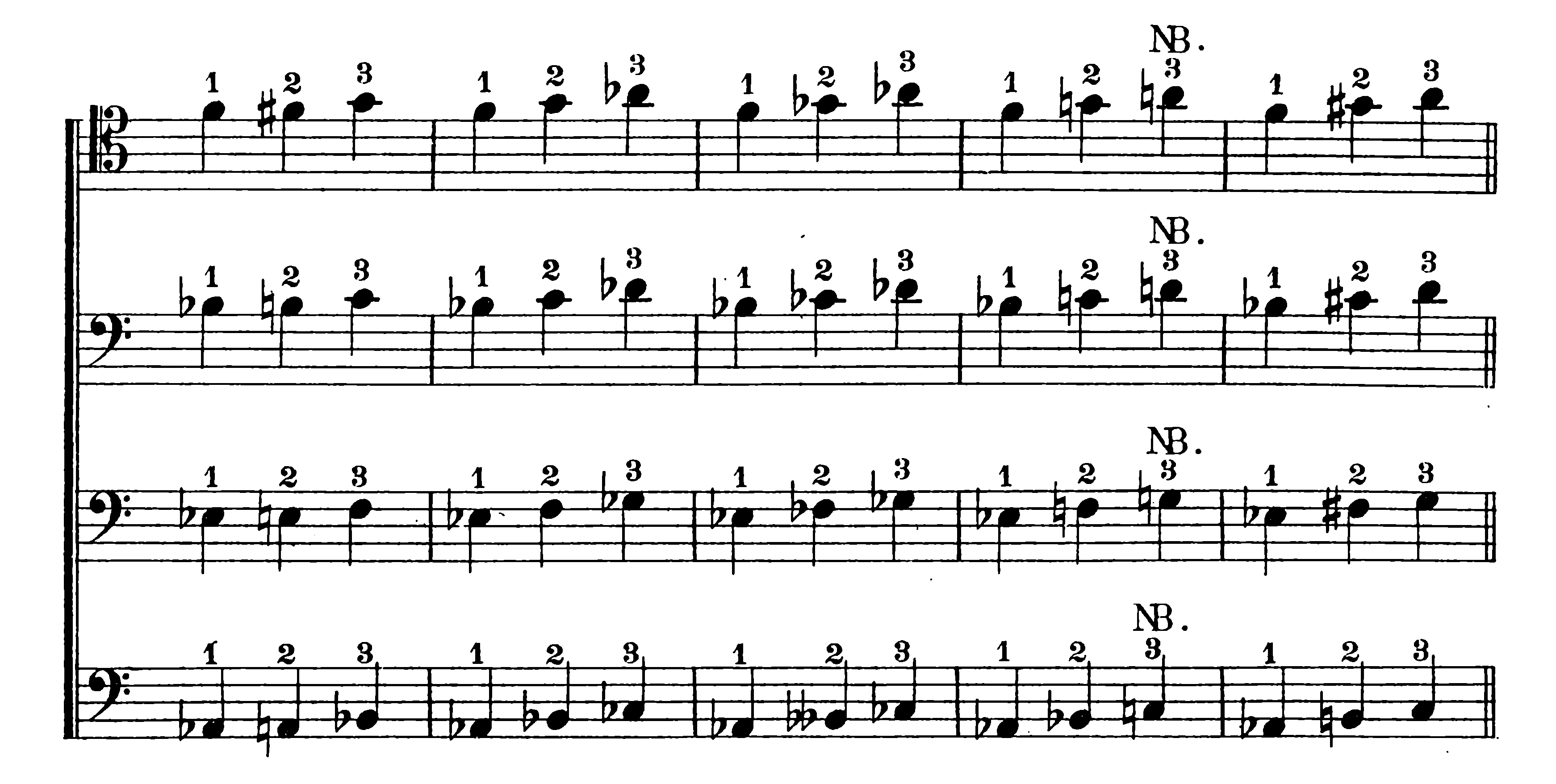

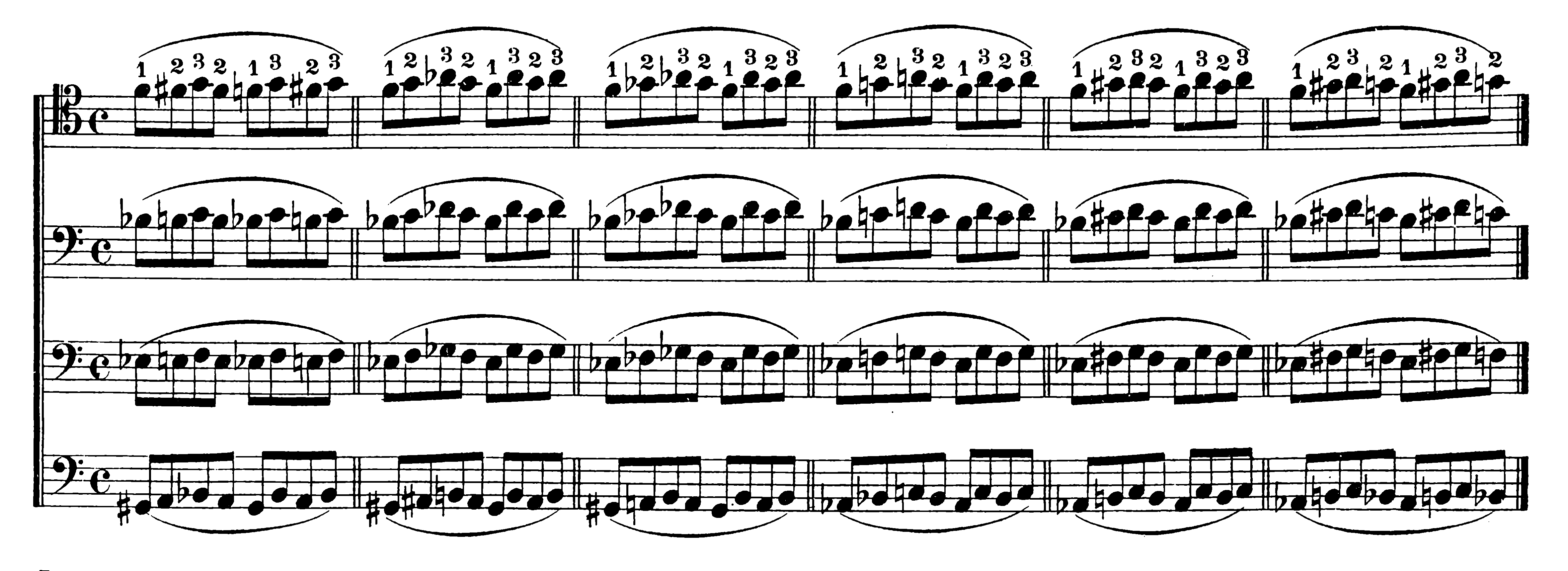

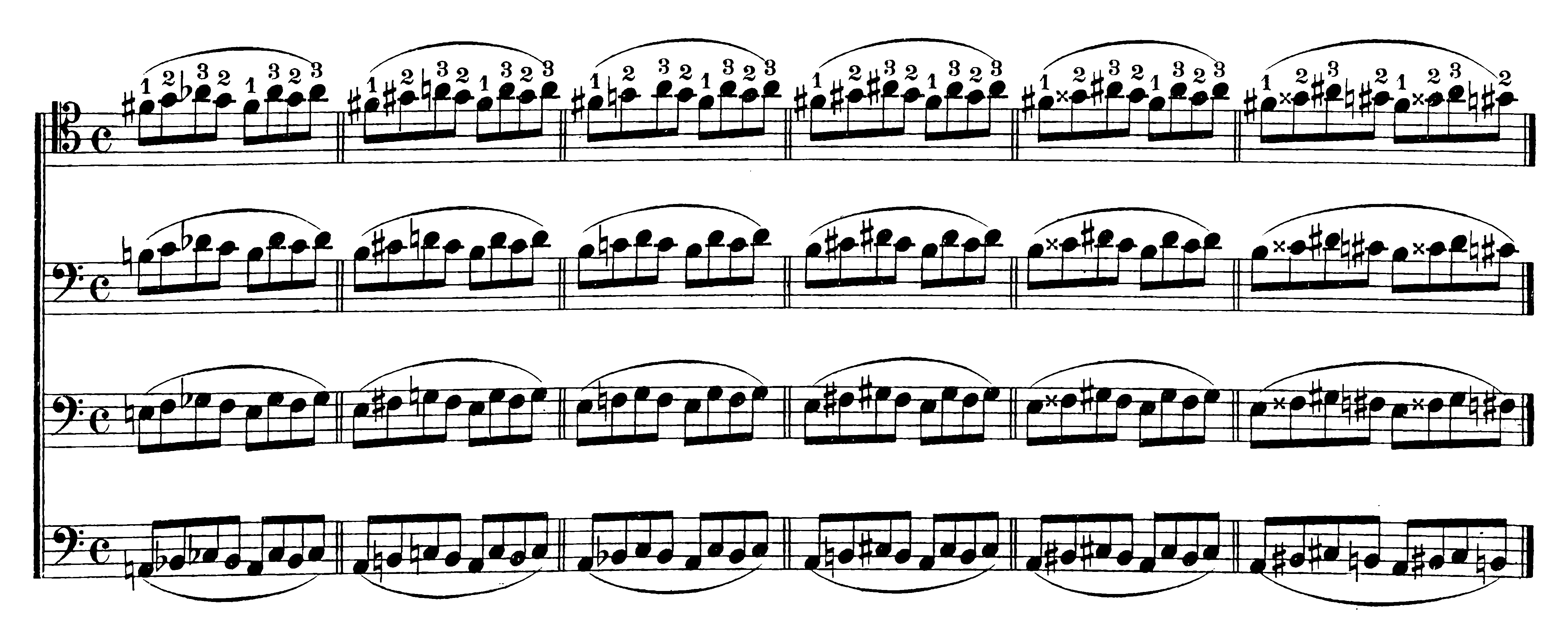

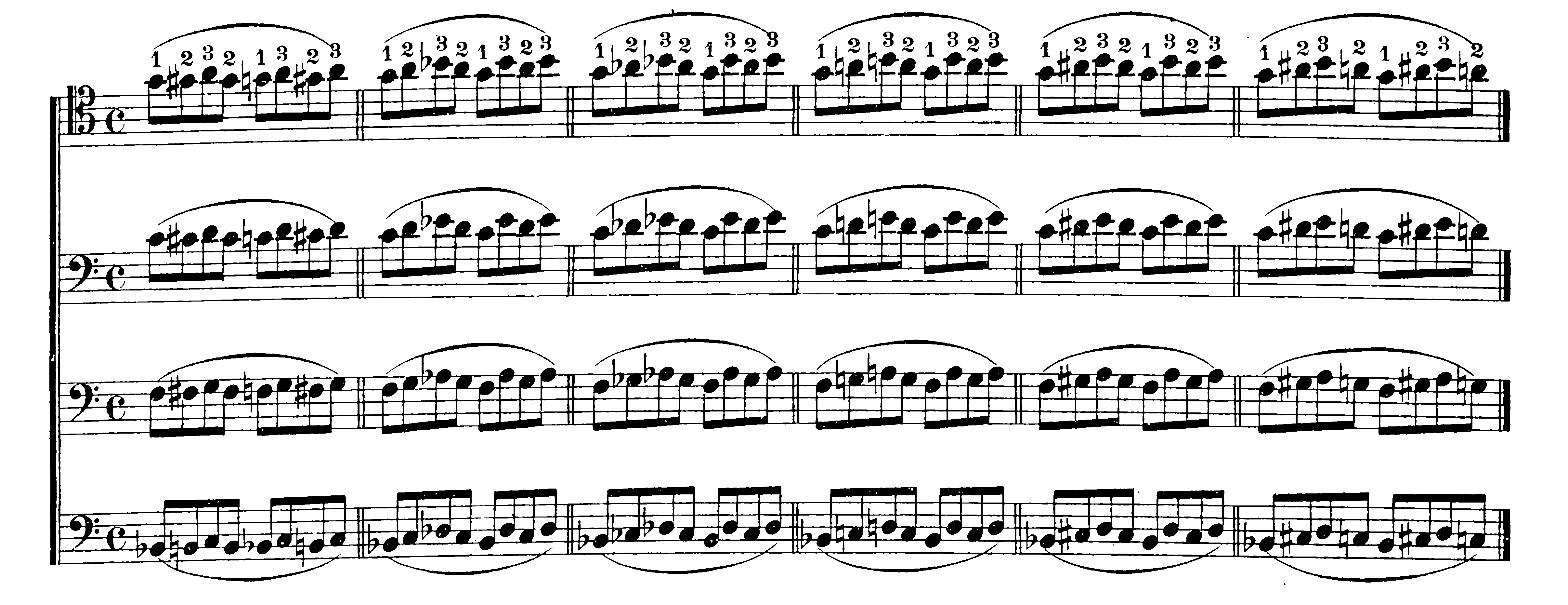

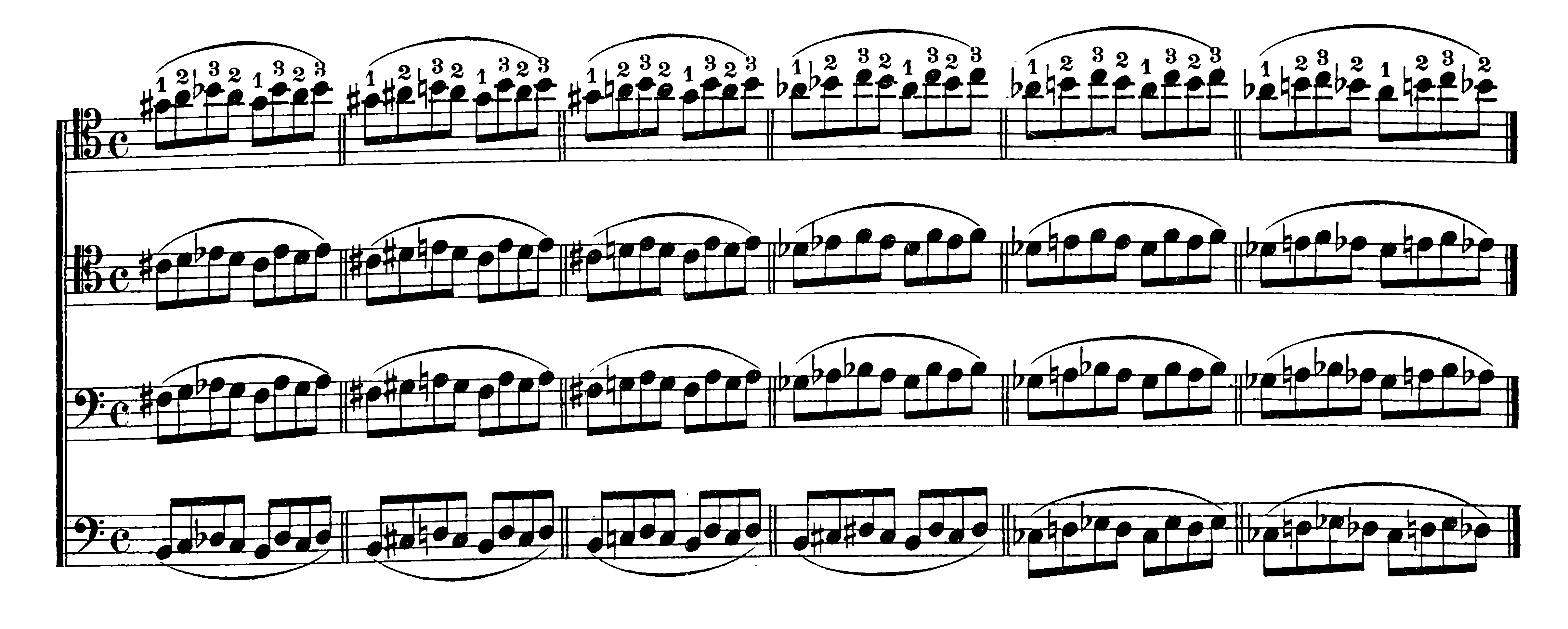

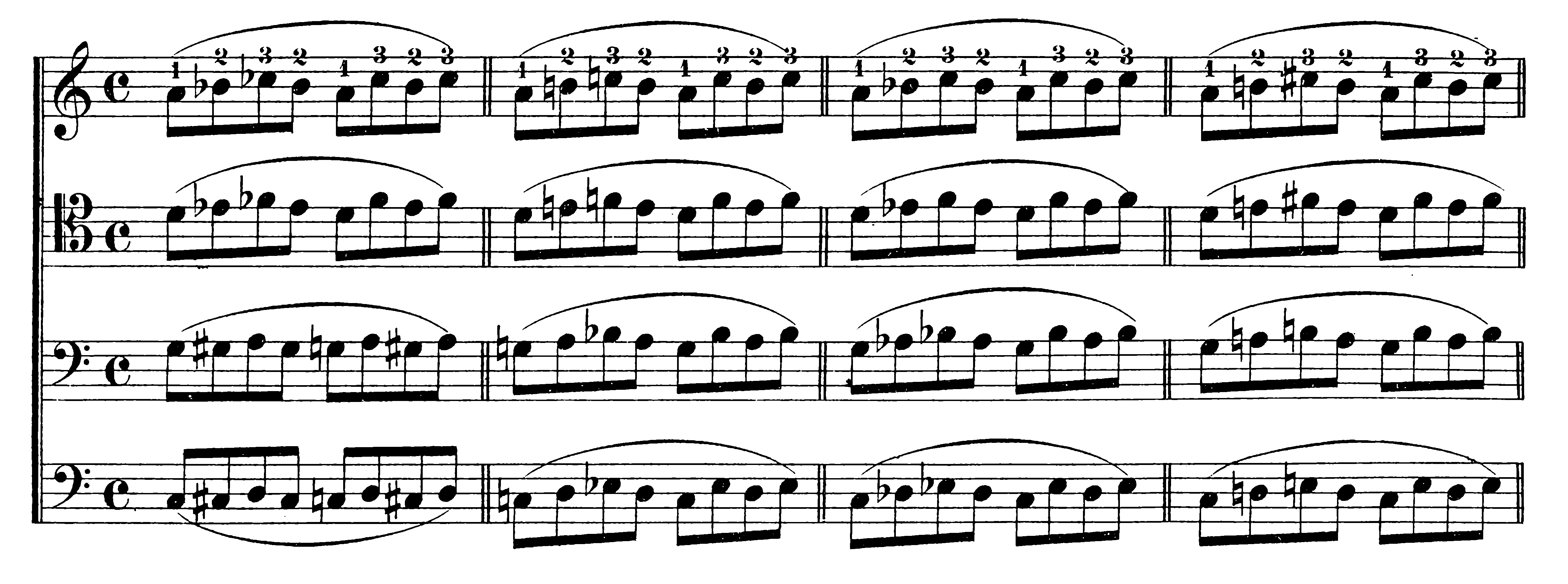

The following exercises show the five fingerings in the higher positions; then similar fingerings for the shifts between the individual higher positions. The rules given in Article III of the previous section remain the same.

Exercises in 4 ½ Position

Exercises in Fifth Position

Exercises in 5 ½ Position

Exercises in Sixth Position

Exercises in Seventh Position

Exercises in Shifting Between Higher Positions

(These exercises are for the A- and D-strings only, since comparable passages seldom occur on the lower strings.)

Example