The Legacy of Bunker Hill

The Place

Location: Kellogg, Idaho

Subjects: mine; community; environment

Time: 1970 - 1980s

The Legacy of Bunker Hill

by Megan Bush

Kellogg, Idaho is a small city nestled into the Silver Valley region in northern Idaho. It is a perfect example of a small American mining town. Located along the Coeur d’Alene River, Kellogg’s stunning geography composed of mountain canyons and dense forest, provided an ideal place for mining. This made it vulnerable to ecological and environmental damage.

Mineral resources are the backbone of the development of Kellogg. According to local legend, a prospector named Noah Kellogg was searching for his donkey nearby for several days on end. During his search for the donkey, Kellogg found an outcropping of a mineral called galena.1 Galena is the primary ore of lead, sulfur and silver, making it incredibly important for several industries. The discovery sparked a mining rush in the local area. Thousands of laborers came to the area to extract untapped, rich resources. Soon after the initial rush, the Bunker Hill Mine incorporated the area into a mining compound that included smelters, underground mining networks, and much more. Bunker Hill’s incorporation provided a turning point for the small town, creating hundreds of jobs, and great economic prosperity for the company. By the early 1900s, the Bunker Hill mine was one of the most productive mines of lead and silver in the entire region.2

The sheer scale of Bunker Hill Mine, and how it led to Kellogg’s environmental destruction, is evident through comparing historical and contemporary photographs of the region. One aerial photograph from 19053, shows the humble beginnings of Bunker Hill and Kellogg. With rolling hills in the background, several small buildings make direct contact with the landscape. While small, it is clear that this local landscape has been devastated by deforestation, and pollution filled the air both above and below ground by smelting and mineral refining. One hundred and twelve years later, a contemporary photograph provides a clear image of how the Bunker Hill Mine has transformed the town.4 By 1981, the mine had grown exponentially, creating a massive compound still clear in photos today. Increasing environmental regulations closed the mine, in 1981, but the pollution still remains.

The environmental devastation that the mine created manifested quickly. By 1910, only twenty-five years after the Bunker Hill mine first became operational, pollution into the Coeur d’Alene River became so bad that local farmers fought back. In a court case named Doty v. Bunker Hill, lawyers representing farmers claimed that twelve million tons of mining waste released into the South Fork of the Coeur d’Alene River had “completely destroyed” portions of their clients’ farmlands.5 The tailings had significantly affected the entire underwater ecosystem and seeped into the surrounding soil. This created irreversible problems for wildlife and people dependent upon the land to feed their families. The Doty v. Bunker Hill case exemplifies what happened throughout the Silver Valley and the Pacific Northwest; where economic development produced environmental destruction, causing struggles among populations that have continued to this day.

By the 1970s, lead poisoning and contamination affected the residents of Kellogg. Tailings poisoned the soil and waterways, but smelting ore at the Bunker Hill mine also made the lead airborne. In the early months of 1972, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found children with lead in their blood in extremely unsafe amounts. Micheal Mix writes in his 2016 book, Leaded, “Kellogg, Idaho, population 5,000 is an unsightly, sickly scab in the midst of one of the world’s healthiest and scenic regions”.6 Traces of lead can still be found in Kellogg residents’ bodies today. When readers and scholars alike think about the environmental destruction caused by large scale mining operations, they tend to forget about the children and new generation brought up in this way of life. The suffering of these children is a haunting reminder of what industries risk in the name of economic prosperity.

The mine closure of the early 1980’s resulted in thousands of people losing their jobs and leaving Kellogg for good. In 2025, the population is down to 2,120 residents, less than half its population during the time that Bunker Hill was at its peak production.7 Mix emphasizes this rapid decline by adding, “The town is dying proof of what can happen if people ignore nature and permit industry to run wild”.8 The long-term social and environmental consequences of the mine continue to shape the landscape and community of Kellogg today. This small town has been forever changed by the intensive extraction industry of the Silver Valley.

Despite these odds, Kellogg has successfully rebranded itself as a beautiful recreational town. From high-scale ski resorts, hotels, and hiking trails, Kellogg offers a wonderful place to visit solo, or with families. The local community continues its efforts to reduce mining pollution and preserve the local landscape, as well as many government agencies. Because of their efforts, the average level of lead in locals’ bloodstreams has dropped over 36 micrograms per deciliter.9 The story of Kellogg, Idaho is just one of many in the PNW, where both promise and peril have shaped the landscape. On one hand, mining created thousands of jobs and tremendous profit for the few. However, it also caused violent class struggle, and damaged human lives, ecosystems, and communities.

Works Cited

- Zodrow, Andru. 2024. “Idaho’s Silver Valley Experienced Mass Lead Poisoning in 1973. Decades Later, Blood Lead Levels Are Coming Down.” NonStop Local KHQ. May 9, 2024.

-

Bunker Hill Mining Corp. 2024. Bunkerhillmining.com. 2024. https://www.bunkerhillmining.com/.

-

Spokane Historical. 2025. https://spokanehistorical.org/items/show/516.

-

“Noah S. Kellogg.” 2025. Miningfoundationsw.org. 2025. https://miningfoundationsw.org/page-1847294. ↩

-

Mix, Michael C.. Leaded : The Poisoning of Idaho’s Silver Valley. Chicago: Oregon State University Press, 2016. Accessed October 3, 2025. ProQuest Ebook Central. ↩

-

Archival Idaho Photograph Collection, University of Idaho Library Digital Collections, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/digital/archivalidaho/items/archivalidaho306.html ↩

-

Mix, 2016, pg. 32 ↩

-

Mix, 2016, pg 127 ↩

-

“Kellogg: Center of Silver Valley - a Town Founded by a Donkey, Spokane Historical” 2025 ↩

-

Mix, 2016, pg 127 ↩

-

Hasz, Emily. 2024. “History and Cleanup.” Bunker Hill / Coeur D’Alene Basin Superfund Site. Bunker Hill / Coeur D’Alene Basin Superfund Site. July 16, 2024. https://cdabasin.idaho.gov/history-and-cleanup/. ↩

Primary Sources

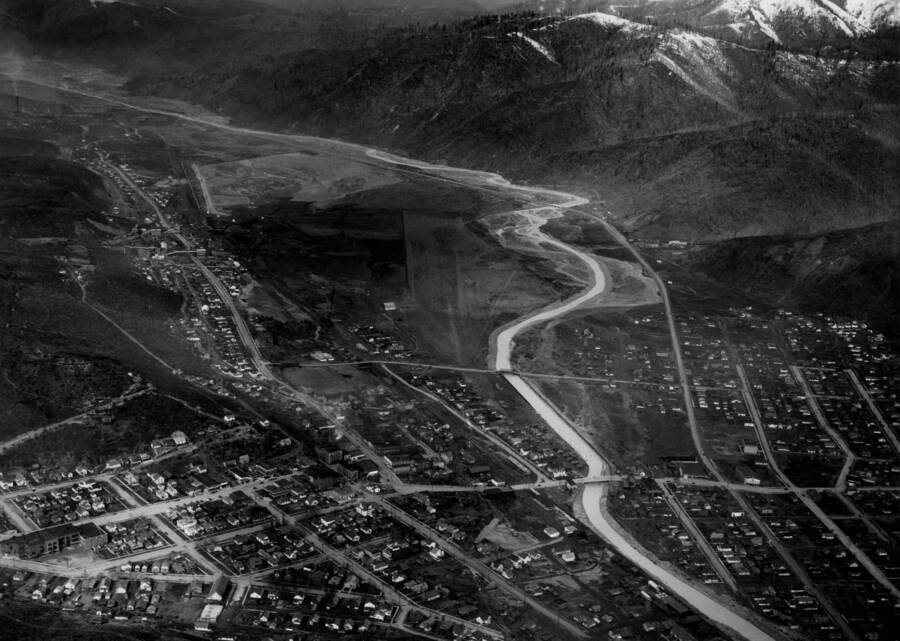

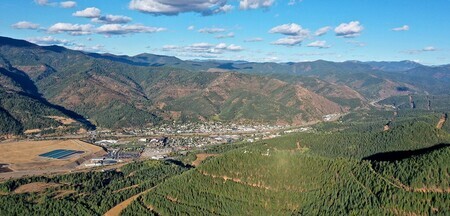

Kellogg, Idaho and Coeur d'Alene River

This photograph shows the connection between the town of Kellogg and the Coeur d'Alene River. As pictured, the river flows directly through the town. Making it a vital source for life and livelihood in Kellogg, Idaho.

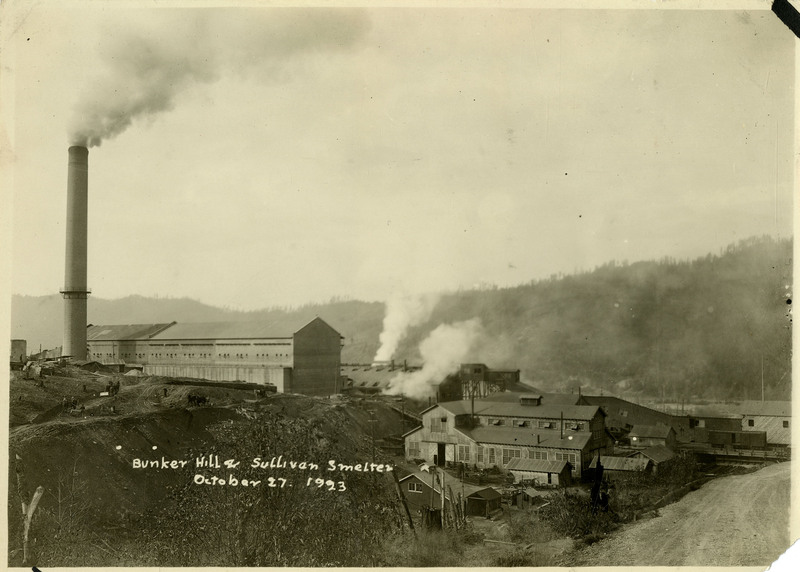

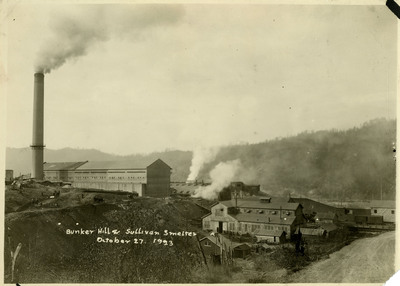

Bunker Hill and Sullivan Smelter

This photograph shows a smelter compound in Kellogg, Idaho. Smelters use heat to extract the desired ore, without impurities. The photograph also shows how the smelters' outputs are entering the environment.

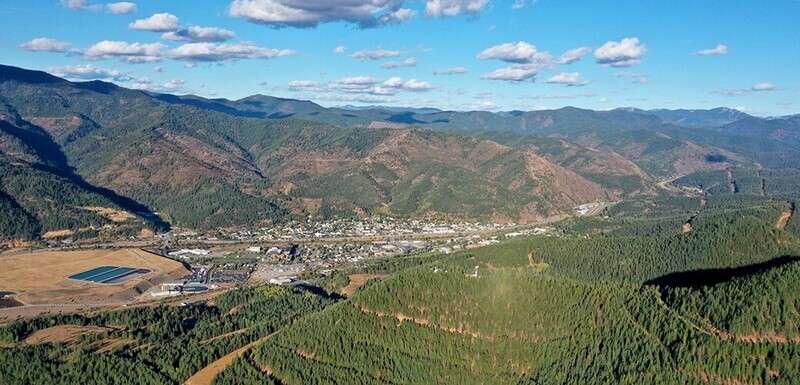

Bunker Hill Mill, Kellogg, aerial

This photograph shows the very beginning of Bunker Hill Mine's development. This photograph shows its large scale, although it began operation less than twenty years before.

Bunker Hill Mining Corp.

This contemporary photograph, posted by Bunker Hill itself, shows how much the mine has grown in the last century. It also provides critical insight into the mountain valley that Bunker Hill rests upon. Giving insights into the modern-day relationship between the local environment and mine.

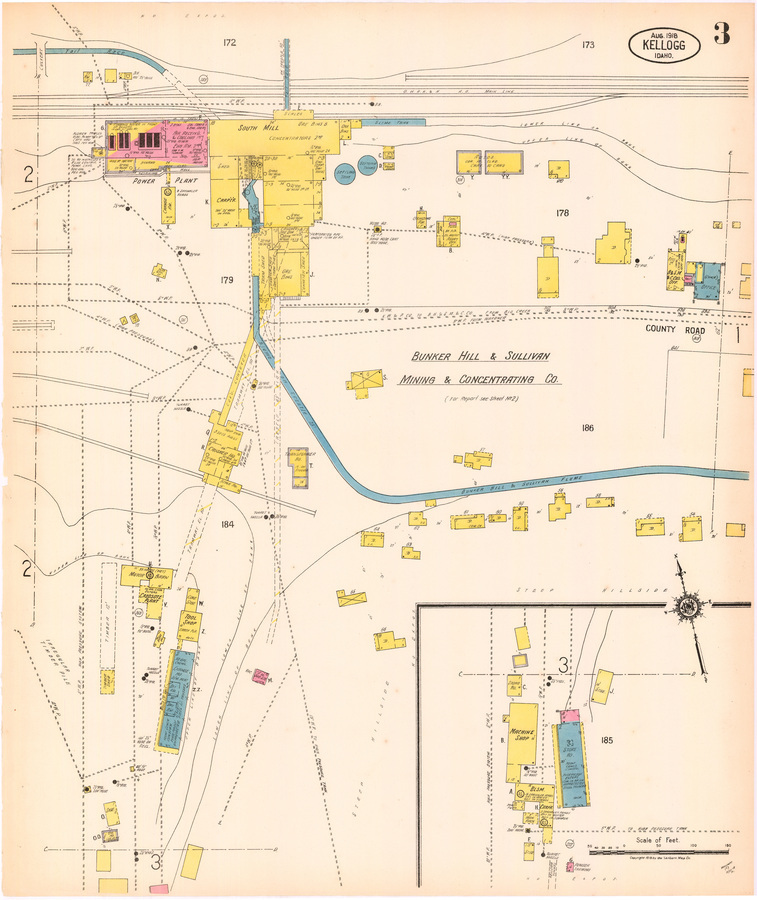

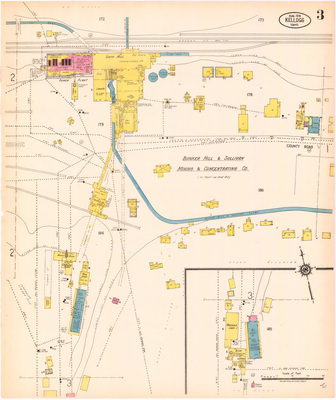

Sanborn map of Kellogg, Shoshone County, Idaho, 1918

This map shows the scale of the Bunker Hill mine in its early foundation. It also shows the number of buildings and systems in place at the time.