Stolen Ground, Essential Hands

The Place

Location: Lewiston, Idaho

Subjects: Chinatown; Lewiston; Mining; Religion

Time: 19th century

Stolen Ground, Essential Hands

by Juniper Harvey-Marose

The city is the manifestation of the broken treaties and the economic engine that relied on Chinese immigrant labor. When visitors walk on the sidewalks of Lewiston today, they walk on the ground that has been contested for generations. The story of broken promises and dispossession can be seen in traces of the past, such as the former Chinese cemetery at Prospect Park and the gravestones that bear Chinese characters in the Normal Hill cemetery.

Lewiston, Idaho, sits at the confluence of the Snake and Clearwater rivers, a site of profound cultural and political conflicts that gives the town a significant place in the history of Idaho and the broader Pacific Northwest. Lewiston lies within the Indigenous territory of the Nimiipuu (Nez Perce people) whose ancestors have occupied the land since time immemorial.1 The establishment and eventual settlement of what would become known as “Rag Town” (Lewiston) offers a valuable case to understand the region’s history.

“Rag Town” cropped up as miners and companies relentlessly pursued gold, encouraging the federal government to continue to break its promises with the Nimiipuu.2 The first treaty signed between federal authorities and the Nez Perce Nation in 1855 guaranteed the Nez Perce sovereignty over their lands within new reservation boundaries that encompassed Lewiston, but the discovery of gold in Pierce, Idaho, in 1860 brought thousands of miners to the area who ignored these boundaries.3

Lewiston was founded in 1861 by European American speculators, settlers, and town builders, establishing a supply center for the nearby mining operations at Pierce, Oro Fino, and Elk City.4 Its mere existence violated the 1855 Treaty.5 The town name “Rag Town” was quickly appointed due to the temporary nature of the first structures, which mainly consisted of tents and canvas-roofed buildings pitched along muddy wagon roads.

The unchecked trespasses and subsequent population explosion directly impacted the Nez Perce, which led the U.S. government to force some Nimiipuu to sign the 1863 Treaty, which reduced the Nez Perce lands by 90%. Nez Perce people today still refer to the 1863 encounter as the “Steal Treaty.”6 The late elder Horace Axtel notes that the 1877 Nez Perce War was partially due to the struggle to preserve traditional religion and cultural ways, threatened by the increasing white encroachment into Nez Perce territory.7

Chinese immigrants were crucial to the first gold rush that sustained Lewiston’s early history and their presence is tightly woven in the town’s history. Mirroring the pattern of other states including California, Chinese miners were initially prohibited from mining.8 When gold yields began to decline in 1865, white miners started to move on from the area and voted to allow Chinese miners to purchase the supposedly “worked out” claims.9 These claims, though less productive in obvious gold, soon revitalized the claims, subsequently sending more money through the town and revitalizing the local economy.10 Their collective efforts brought much-needed economic and commercial benefits, ensuring that Lewiston was not “abandoned to experience a ghost town’s fate.”11 Lewiston quickly became a prominent trading center for the area, and Chinatown located on First Street grew quickly, especially in the winter months, when the freezing weather halted placer mining in the outlying areas.12

Although the popular story of Chinese immigrants in the United States tells of their search for economic prosperity in mining, the Chinese American population played a crucial function in the city in other roles, including as entrepreneurs and support staff, often working for lower wages than their European American counterparts.13 Chinese laborers included laundrymen, cooks, merchants, gardeners, distillers, and pack train operators who carried supplies to miners in the Idaho wilderness. This sustained the economic vitality of the town and played a critical part in preventing Lewiston from becoming a ghost town after the initial rush.14 Chinese Americans acted as a “vital economic bridge” which linked the early mining networks to the later agricultural and timber base.15

Lewiston’s Chinatown, which was located on First Street and between B and C Streets, was a meticulously organized and reportedly functioned like a Chinese village, as an observer noted that the layout of Lewiston’s Chinatown had stores facing the street, with narrow lanes that led to homes near the rear.16 The combination of homes and businesses made a prominent trading center and provided the Chinese community with established and maintained cultural institutions. One such institution, which was central to the community, was the Beuk Aie Temple (Liet Sing Gung) and the Hip Sing Tong. The Beuk Aie Temple, meaning “palace of many gods,” served as the community’s place of worship and incorporated the beliefs of Taoism, Buddhism, and traditional folk practices, with Beuk Aie (the God of the North) as the principal deity.17 Nearby the temple was the Hip Sing Tong, locally known as the “Chinese Masonic Lodge,” and was a fraternal organization that provided social interaction and lessons on “honesty and fair dealing” to the members.18

Lewiston’s Chinatown fostered a sense of community, but the crowded conditions and older, sometimes dilapidated, buildings made the area vulnerable to potential disaster, including a destructive fire that swept through Chinatown on November 19, 1883.19 The fire started at about 4:30 in the morning, destroying and necessitating the demolition of thirteen structures.20 The fire destroyed all the buildings on the north side of D Street and most buildings between C and D streets and First and Second Streets, all of which were occupied by Chinese persons, with only two European American businesses also destroyed.21 Although the cause was never discovered, most European American residents believed the Chinatown to be an eyesore and that the only loss was “the rental income the owners were getting from the Chinese.”22 However, the Chinese community suffered the loss of their homes and possessions, including “a number of ducks and chickens.”23 Although the destruction devastated the community, the Chinese Temple was not affected, situated a few blocks away, which enabled the community to maintain their spiritual center.24

The story of Lewiston, Idaho, is representative of the wider history of Idaho and the Pacific Northwest. The city owes its existence to resource extraction, which triggered Indigenous displacement and then required cheaper immigrant labor of marginalized groups, such as the Chinese, to maintain the economy post-boom.25 Although Lewiston never forcibly removed the Chinese residents, like other nearby towns such as Bonners Ferry and Moscow, Idaho, the history of Lewiston reflects the same anti-Chinese sentiment of the time, evident in discriminatory tax laws and rhetoric.26 The creation of Lewiston, supported by Chinese labor, is a clear example of how economic growth and non-Native landscapes were built on extraction and injustice, from stolen Nimiipuu land to exploited Chinese labor, beginning with the forceful dispossession of the Nez Perce, and followed shortly thereafter with the exploitation of Chinese immigrants who were essential to the area’s survival.27

Works Cited

-

Nez Perce Tribe, Treaties: Nez Perce Perspectives, 1. ed, Confluence Press, 2003, 2. ↩

-

Nez Perce Tribe, Treaties, x. ↩

-

Nez Perce Tribe, Treaties, 41-43. ↩

-

Priscilla Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” Unpublished manuscript, 1996, University of Idaho Asian American Comparative Collection, Moscow, Idaho, 8. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” 8; Nez Perce Tribe, 41. ↩

-

Nez Perce Tribe, Treaties, 42. ↩

-

Nez Perce Tribe, Treaties, 49. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” iii. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” iii. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” iii, 79. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” 163. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” 50. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” 79. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” iii, 51, 67, 84. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” 194. ↩

-

Campbell, quoted in Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” 57. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” 107-108. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” 120. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” 58; “Fire in Lewiston,” Lewiston Daily Teller, November 22, 1883, 3. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” 58. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” 58. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” 58; “Fire in Lewiston,” 3. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” 58. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” 58. ↩

-

Wegars, 193; Nez Perce Tribe, 34. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” 26, 29. ↩

-

Wegars, “Chinese at the Confluence,” 163, 165. ↩

Primary Sources

Children's Silk Hat

Decorated traditional chinese children's hats were given to children in the early twentieth century to protect them from evil and heartfelt blessings for good fortune and health. The embroidery on the hat represents traditional chinese culture, embracing prosperity, longevity, happiness, success, abundance, and luck. Hats designed with ferocious animals were believed to ward off evil spirits, bestowing strength and power on the child.

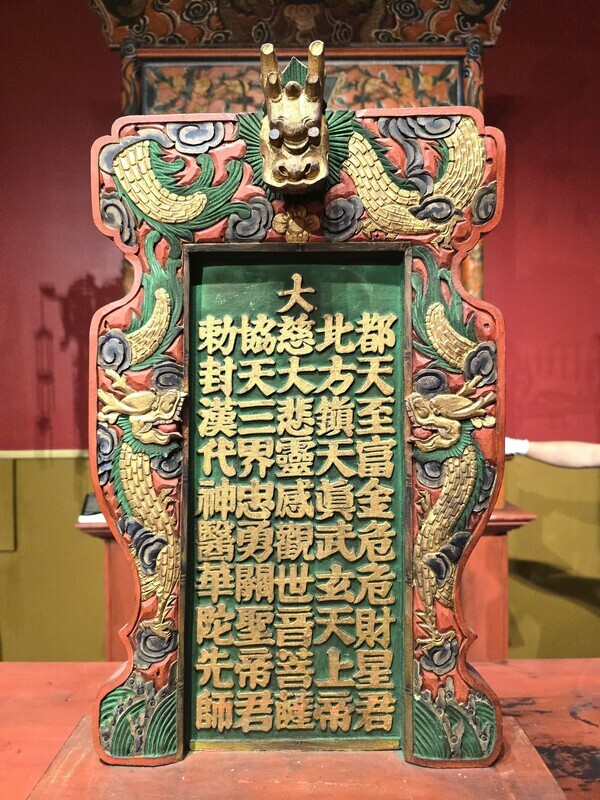

Spirit Tablet

The tablet found in the beuk aie temple collection signifies the establishment of a chinese and cultural community in the american west during the nineteenth century. These tablets embody the connections to ancestral worship and temple-based spiritual traditions brought back from southern china, representing the continuity within the diaspora. The detailed tablet shows how chinese immigrants in lewiston maintained transnational cultural identities and asserted community presence and cohesion in lewiston.

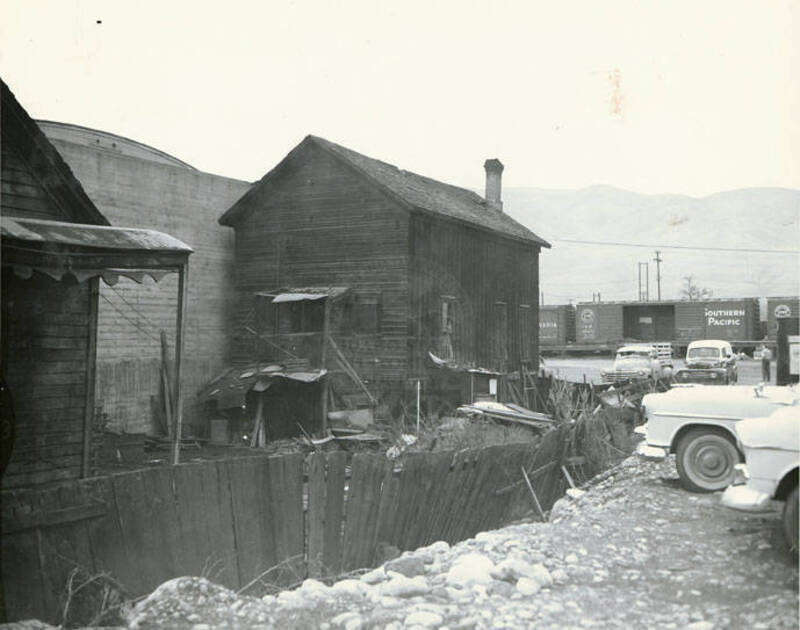

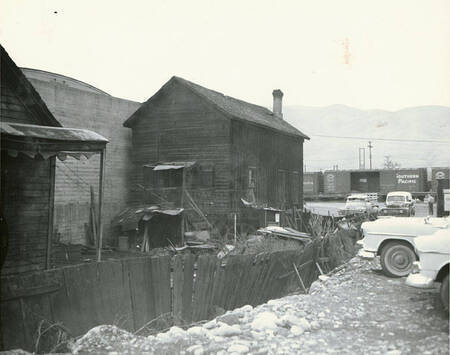

Old Chinese Masonic lodge, 1959

The hip sing tong, locally known as the Chinese Masonic lodge, was an important social institution established in Lewiston in the 1860s, designed as a fraternal organization dedicated to assisting its “unfortunate brothers.” the organization aimed to be fraternal like the “white man's lodges,” and was an important part of the Chinese community, having about 60 members by 1904, which was nearly all of the Chinese residents in the city at the time. adopting the name “Chinese Masonic Lodge,” the Hip Sing Tong sought more acceptance from the European American community, particularly because the traditional Chinese word “tong” was often associated with illegal activities and “tong wars.”

Power of the Press

The photo represents the Lewiston Morning Tribune's modern press building, which shows the city's ongoing evolution and endurance in a changing media landscape. The location is significant as it occupies the former site of Lewiston's old Chinese Hip Sing Tong building and the Beuk Aie temple, which were important centers for the Chinese community, demolished in 1959. The picture shows the progress and loss, symbolizing the development that is acquired at the loss of Lewiston's Chinese heritage. The Site Is Located In Downtown Lewiston, Idaho, Near The Confluence Of The Clearwater And Snake Rivers, Which Once Contained The Historic Chinatown. Originally Housing The Hip Sing Tong And Beuk Aie Temple, Central Institutions To The Chinese Community. It Is Now The Modern Lewiston Morning Tribune Building.

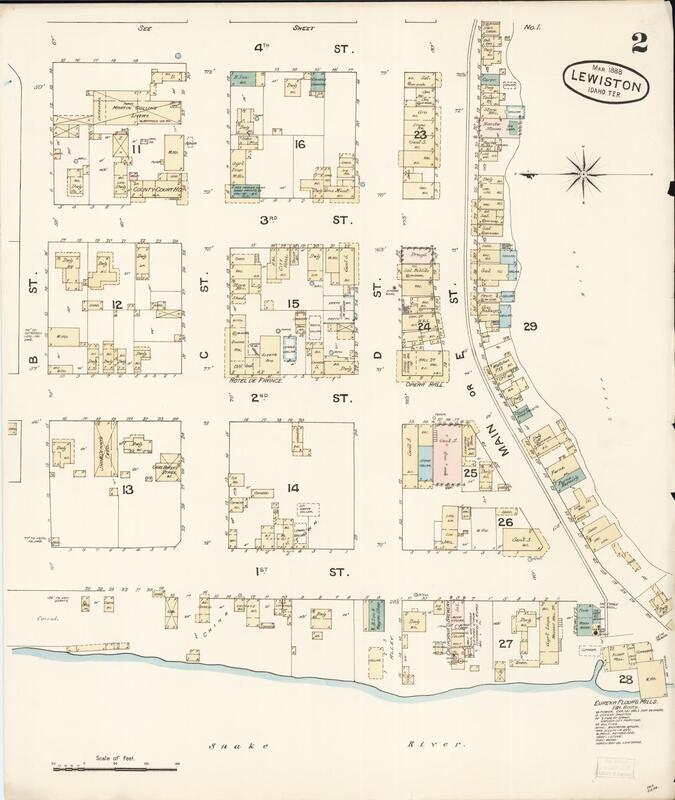

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Lewiston, Nez Perce County, Idaho

The map shows one of the earliest detailed records of Lewiston's Chinatown, showing the physical presence of the Chinese community in the late nineteenth century. This map illustrates the Chinese community's establishment of homes, businesses, and other establishments near the commercial core of Lewiston, despite facing social and legal marginalization.