Camp Easter Seal

The Place

Location: Lake Coeur d'Alene, Idaho

Subjects: summer camps; Coeur d'Alene tribe; colonization

Time: circa 1950s; circa 1970s

Camp Easter Seal

by Jose Montelongo

In a valley surrounded by grand mountains and lush vegetation with picturesque views, the city of Coeur d’Alene possesses some of the prettiest land in North Idaho and is a seasonal home to our national bird, the bald eagle.1 South of the city, the Coeur d’Alene lake hugs the city reflecting sunshine off its crystalline blue waters. Spanning 26 miles wide, with walkable beaches that extend for 135 miles, its glacial waters, full of salmon and bass, are loved by all who get to witness it.2 Its unique environment provides ample recreational opportunities which humans have taken full advantage of. In 1950, Washington State University (WSU) and the State Society for Crippled Children and Adults (SSCCA), founded Camp Manitowish, with the help of Roger Larson, an instructor of physical education at WSU.3 The camp was founded to enrich the lives of adults and children who could not enjoy outdoor recreational opportunities because of their physical disabilities. This essay will expand on the history involving the Coeur d’Alene people and the land, examining how Camp Manitowish was established during the 1950s in an effort to bring more historical context to readers and visitors alike.

For millennia, the Schitsu’umsh tribe or Coeur d’Alene people called the Pacific Northwest (PNW) home, living and thriving off the rich land.4 In an era of “Manifest Destiny,” 19th century westward expansion quickly populated the PNW with Euro-American homesteaders.5 All the Indigenous people who lived during this time were negatively affected by this expansion—the Coeur d’Alene tribe was no exception nor was colonization exclusive to tribes living in the PNW. Due to an influx of colonizers and in effort to assimilate the Coeur d’Alene tribe to western culture, in 1873, President Ulysses S. Grant issued an executive order confining the tribe to the Coeur d’Alene reservation. Despite their ancestorial ties with 5 million acres of land that spanned through the PNW, Montana, and Canada, only a mere 500,000 acres were allocated for the tribe.6 In the years that followed, the Coeur d’Alene tribe gradually continued to lose land due to unfair federal policies and westward Euro-American expansion.

Established in 1878, General William T. of the Union created a military base named Fort Sherman.7 Dense in minerals and ores, Fort Sherman’s lucrative surroundings attracted Euro-American homesteaders who searched for economic opportunities.8 Due to a boom in the area’s population, Fort Sherman quickly became an incorporated city under a new name, Coeur d’Alene. Ironically, despite being renamed Coeur d’Alene, the tribal reservation was later reduced in 1891, outside of the city’s boundaries.9

In an effort to assimilate Indigenous peoples to Euro-American culture, the federal government passed the Dawes Act, which requisitioned tribal land. Each member of the Coeur d’Alene tribe was allotted 160 acres of land on their reservation. In doing so, the tribe was expected to adopt Euro-American farming practices and convert their beliefs to Christianity. After the redistribution of land, the tribe owned 104 thousand acres of the Coeur d’Alene reservation. The remaining lands were unfairly sold to Euro-American homesteaders, effectively decreasing the original reservation size.10 Sorrow and anger filled the tribe as a devastating 310,000 acres of land were lost, including the magical Coeur d’Alene lake.11 The Dawes act allowed Euro-American expansion to continue and develop economically and recreationally, which included the opening of Camp Manitowish, a summer camp for adults and children with physical disabilities.

The camp was founded in the summer of 1950 by WSU and SSCCA. Located on a section of Coeur d’Alene Lake, the camp was first established on Point McDonald. Roger Larson, a physical education instructor at WSU, was also a prominent figure in opening the summer camp. Larson worked alongside Ruth Radar in a co-director position during its time of operation. Additionally, the camp underwent several name changes, even changing its name shortly after its founding to Camp Easter Seal in 1955. Subsequently, the camp was moved to Point Cotton Bay, another section of Coeur d’Alene lake (47°26’47.3”N 116°50’19.0”W). Camp names that followed included Camp WSU in 1977, and finally Camp Larson in 1980 following Larson’s retirement.12

From 1955 to 1976, Camp Easter Seal was operated, maintained, and staffed through WSU’s physical education department.13 Camp counselors were primarily WSU students studying physical education. These WSU students received credit towards their degree and gained valuable hands-on experience.14 A physical therapist, nurse, and doctor were also present on the campgrounds. Camp Easter Seal’s primary goal was to provide an authentic summer camp experience for children and adults with physical disabilities. They participated in typical summer camp activities such as arts and crafts, swimming, and sports.15 Unfortunately, the fun came to an end after being renamed Camp Larson. As a result of the outdated infrastructure, the summer camp was closed and sold to the Coeur d’Alene tribe for 1.4 million dollars.16

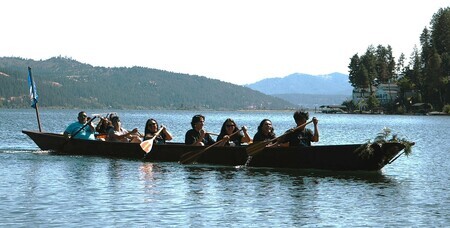

Lake Coeur d’Alene continues to capture the attention of those who are fortunate enough to view its sparkling blue waters. The lake’s unique history tells two prominent stories. One of dreaded colonization and injustices faced by the Coeur d’Alene tribe, the other, a past full of summer enriching camp activities for the disabled. Understanding the land’s historical context allows visitors and readers to enjoy Lake Coeur d’Alene with greater nuance. Today, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe enjoys the lake-front area, where it has opened its own summer camp. Despite the Supreme Court’s ruling that the Coeur d’Alene Tribe owns the lower portion of the lake, it is the only water-front property held by the Tribe today.

Works Cited

-

“Coeur D’Alene Eagle Watching | Higgins Point Eagles,” Visit North Idaho, last modified November 30, 2023, https://visitnorthidaho.com/activity/bald-eagles-lake-coeur-dalene/. ↩

-

“Is Coeur D’Alene Lake a Reservoir or Lake?,” Avista Utilities - An Energy Company, accessed November 17, 2025, https://www.myavista.com/connect/articles/2018/05/true-or-false. ↩

-

“Washington State University Camp Larson Scrapbooks and Photographs,” Archives West, accessed November 17, 2025, https://archiveswest.orbiscascade.org/ark:/80444/xv649443#id22. ↩

-

“Time Immemorial,” Coeur D’Alene Tribe, accessed November 17, 2025, https://www.cdatribe-nsn.gov. ↩

-

HISTORY.com Editors, “Manifest Destiny,” HISTORY, last modified April 5, 2010, https://www.history.com/articles/manifest-destiny. ↩

-

“Establishing Reservations,” Coeur D’Alene Tribe, accessed November 17, 2025, https://www.cdatribe-nsn.gov/. ↩

-

“History & heritage,” Visit Coeur d’Alene, last modified July 12, 2017, https://coeurdalene.org/play/history-heritage/. ↩

-

“Keys to significance,” Silver Valley & Lake Coeur d’Alene Watershed, last modified June 10, 2020, https://nationalheritagearea.wordpress.com/significance/. ↩

-

“A developing community,” Kootenai County, ID | Official Website, accessed November 17, 2025, https://www.kcgov.us/589/A-Developing-Community. ↩

-

Lifelong Learning Online - The Lewis & Clark rediscovery project, “Manifest Destiny: Allotment,” University of Idaho Library | University of Idaho Library Home, accessed November 17, 2025, https://www.lib.uidaho.edu/digital/L3/ShowOneObjectSiteID50ObjectID816.html. ↩

-

Lifelong Learning Online - The Lewis & Clark rediscovery project, “ Manifest Destiny” ↩

-

” Washington State University Camp Larson” ↩

-

“Camp Easter Seal Plans To Entertain 40 Children,” Idaho Statesman, May 24, 1956, 28. ↩

-

Communications Staff, Washington State University, “Portrait honors memory of professor,” WSU Insider, last modified June 19, 2007, https://news.wsu.edu/news/2007/06/19/portrait-honors-memory-of-professor/. ↩

-

” Washington State University Camp Larson” ↩

-

H. Sudermann, “Camp Larson—a heritage reclaimed,” Washington State Magazine, last modified August 1, 2005, https://magazine.wsu.edu/2005/08/01/camp-larson-a-heritage-reclaimed/#:~:text. ↩

Primary Sources

Annual report adult handicap camp summer session 1979

The primary source relates to my place because it allows us to further understand how Camp Larson was managed. It also shows how the camp served handicap adults.

Washington State University Camp Larson scrapbooks and photographs

The picture shows what a typical night might have looked like at Camp Larson.

Coeur d'Alene Tribe celebrates the renaming of Camp Larson to Ch ułts'e'l

The land where camp larson was settled on originally belonged to the Coeur d'Alene Tribe.

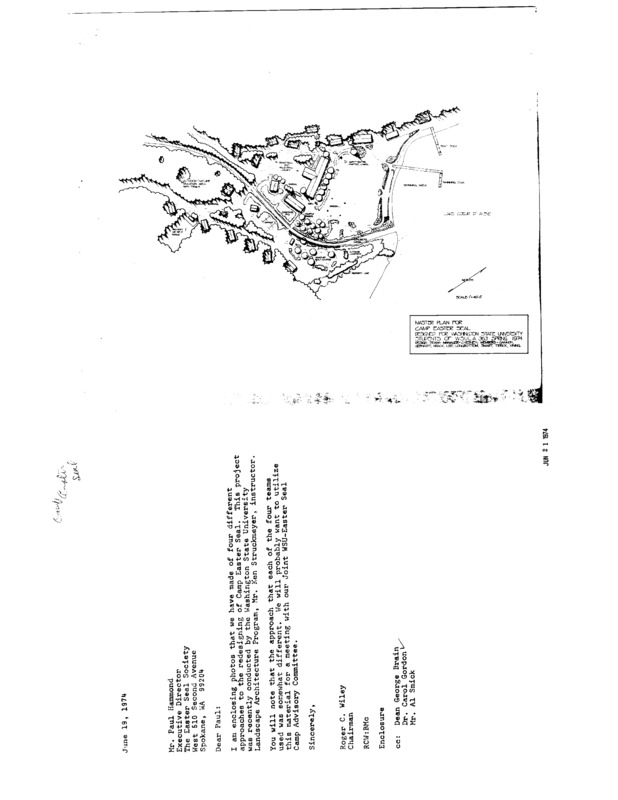

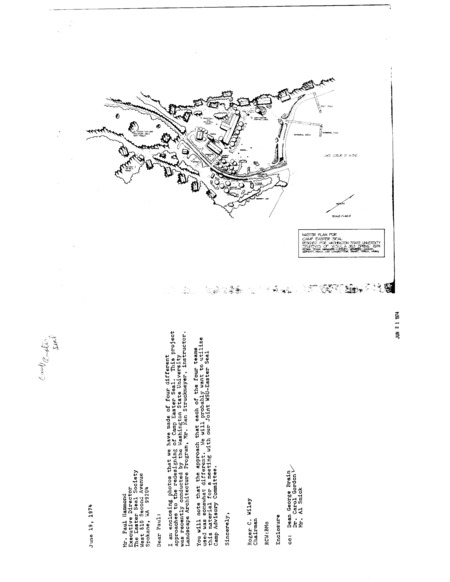

Preliminary Guide to the Roger C. Larson Papers

These maps give us an insight of what Camp Easter Seal might have looked like. The camp is reimagined in four different ways from the WSU Architecture program.