The Big Burn: Class War in the Ashes

The Place

Location: Wallace, Idaho

Subjects: Labor; Colonialism; Segregation; Environment

Time: 1910s

The Big Burn: Class War in the Ashes

by Wade Wade

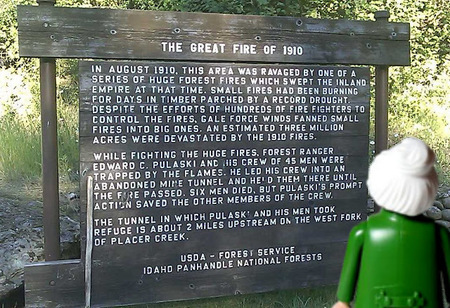

In the popular imagination, the Great Fire of 1910 is remembered as a heroic battle between man and nature. If you visit the roadside markers in Wallace, Idaho, or the museums of the Silver Valley, the story is presented as a romanticized “crucible” where U.S. Forest Service rangers fought a “red demon” to save the nation’s timber. The narrative centers on individual heroism, most notably Ranger Ed Pulaski, who saved his crew by holding them at gunpoint in a mine tunnel as the fire raged over them.1 However, this “great man” history obscures the political and industrial machinery that set the stage for the disaster. The 1910 fire was not merely an “act of God”; it was an industrial catastrophe born of colonial arrogance, corporate greed, and the erasure of Indigenous knowledge.

To understand the Big Burn, one must first look at the land’s history of management. For millennia, the Coeur d’Alene, Salish, and Nez Perce peoples managed these forests with “fire stewardship,” intentional, low-intensity burns that cleared underbrush and prevented massive fuel buildups. By 1910, the U.S. Forest Service had criminalized these practices, viewing fire not as an ecological necessity but as a military enemy that threatened timber profits. Agency leaders ridiculed Indigenous knowledge as “Paiute forestry,” a racist slur used to dismiss controlled burning as primitive.2

This colonial mindset turned the Northern Rockies into a tinderbox, but it was industrial capitalism that lit the match. The “Inland Empire” was an extraction colony, and the primary ignition source for the disaster was the newly constructed Chicago, Milwaukee, and Puget Sound Railway. These coal-powered locomotives, struggling up the steep grades of the Bitterroots, spewed red-hot cinders into the tinder-dry slash piles left by loggers.3 While the railroads extracted the wealth, the land paid the price; it is estimated that these trains were responsible for hundreds of small fires that eventually merged into the inferno.4

When the inevitable blowup occurred, the burden of fighting fell not on the timber barons but on the marginalized. The Forest Service emptied the saloons and pool halls of Spokane and Butte, recruiting unemployed immigrants and drifters who had little equipment or experience to dig the fire lines.5 When the situation became dire, the federal government deployed the Buffalo Soldiers (the 25th Infantry), a segregated unit of Black troops. Their arrival momentarily doubled the Black population of Idaho.6 These men brought order to the chaos, policing the evacuation of Wallace and saving the town of Avery by setting backfires alongside Japanese railroad workers.7 These Japanese laborers, just months after celebrating the Emperor’s birthday, worked side-by-side with Black soldiers to save towns that likely would have excluded them in peacetime.

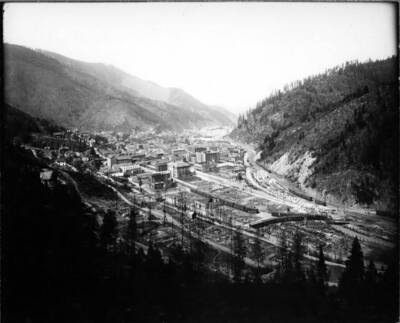

The fire itself exposed the stark class disparities of the region. As the firestorm descended on Wallace, trains were marshaled to evacuate women and children, but the recovery was unequal. The fire incinerated the eastern end of town, often home to the transient workforce and the poor, reducing it to “brick shells and ash.”8 Even the heroes were discarded once the smoke cleared. Ranger Pulaski, celebrated on bronze plaques today, suffered temporary blindness and permanent respiratory damage from the fire. He spent the rest of his life struggling to receive compensation from the government for his injuries, a bitter reminder that the agency valued his legend more than his life.9

The legacy of 1910 is the silence of the modern forest. The “total suppression” policy enacted after the fire, the “10 A.M. Policy,” was a rejection of Indigenous science that has left the West with fuel-choked, unhealthy forests.10 Today, the “dog-hair” thickets of the Bitterroots stand as a monument to a policy that tried to outlaw fire, only to ensure that when it returns, it burns hotter and faster than ever before.

Works Cited

-

“The 1910 Fires,” Forest History Society, accessed November 12, 2025, https://foresthistory.org/research-explore/us-forest-service-history/policy-and-law/fire-u-s-forest-service/famous-fires/the-1910-fires/. ↩

-

“A Test of Adversity and Strength: Wildland Fire in the National Park System,” National Park Service, accessed November 12, 2025, https://www.nps.gov/subjects/fire/upload/wildland-fire-history.pdf. ↩

-

The Big Burn: Exploring the Great Fire of 1910 in Idaho & Montana,” Rails to Trails Conservancy, accessed November 12, 2025, https://www.railstotrails.org/trailblog/the-big-burn/. ↩

-

“The Great Fire of 1910,” CAFSTI, accessed November 16, 2025, https://www.cafsti.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Great-Fire-of-1910.pdf ↩

-

“The Great Fire of 1910,” CAFSTI, accessed November 16, 2025, https://www.cafsti.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Great-Fire-of-1910.pdf ↩

-

“The 1910 Fires,” Forest History Society. ↩

-

“1910 FIRES,” NPS History, accessed November 16, 2025, https://npshistory.com/publications/usfs/region/1/great-1910-fires.pdf ↩

-

“The Big Burn: Exploring the Great Fire of 1910,” Rails to Trails Conservancy. ↩

-

E.C. Pulaski, “Surrounded by Forest Fires,” Forest History Society, accessed November 12, 2025, https://www.google.com/search?q=https://foresthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Surrounded-by-Forest-Fires-t-By-E.C.-Pulaski.pdf ↩

-

“The Big Burn of 1910 and the Choking of America’s Forests,” PERC, accessed November 12, 2025, https://www.perc.org/2022/06/23/the-big-burn-of-1910-and-the-choking-of-americas-forests/ ↩

Primary Sources

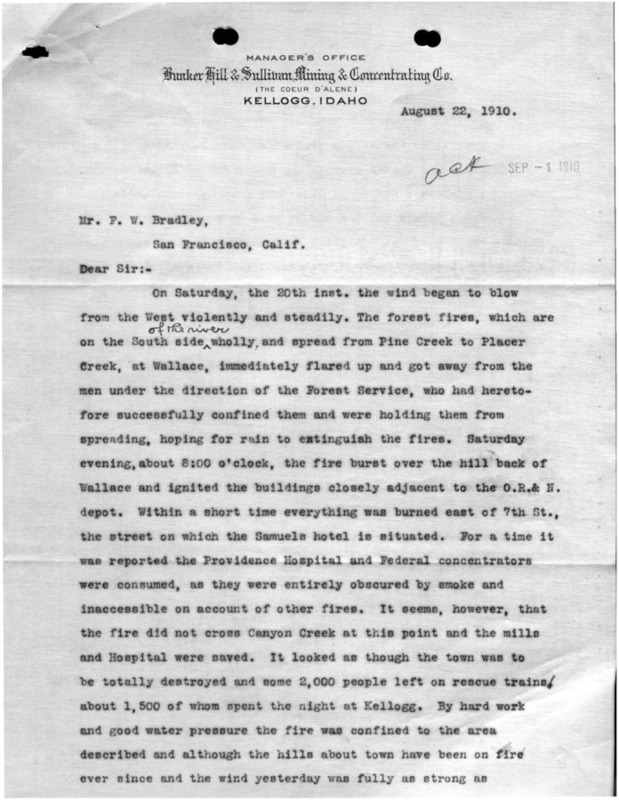

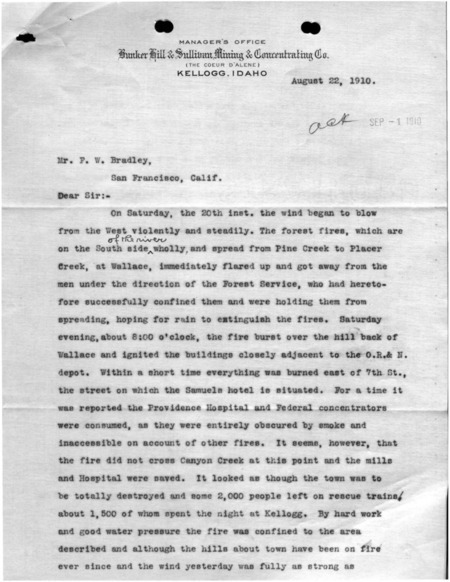

Forest Fire, 1910 - Correspondence [02]

This letter is a significant primary source documenting the direct impact of the Great Fire of 1910 on Wallace. It provides a first-hand account of the fire destroying the eastern part of the town and forcing the evacuation of around 2,000 residents. The correspondence also records the human toll the disaster took on the community, noting the loss of life and the strain on local hospitals.

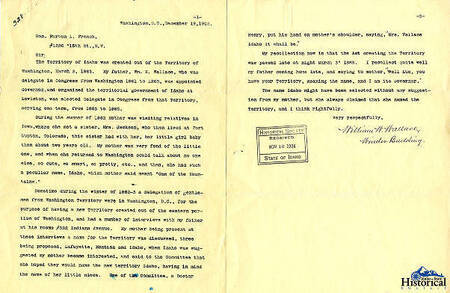

William W. Wallace Letter to Burton L. French

This letter's significance to Wallace is contextual, as it details the origin story of Idaho's name. It presents a personal narrative that credits the wife of William H. Wallace, the first territorial governor, with successfully proposing the name "Idaho". The document provides historical background for the identity of the state in which Wallace is a prominent historical town.

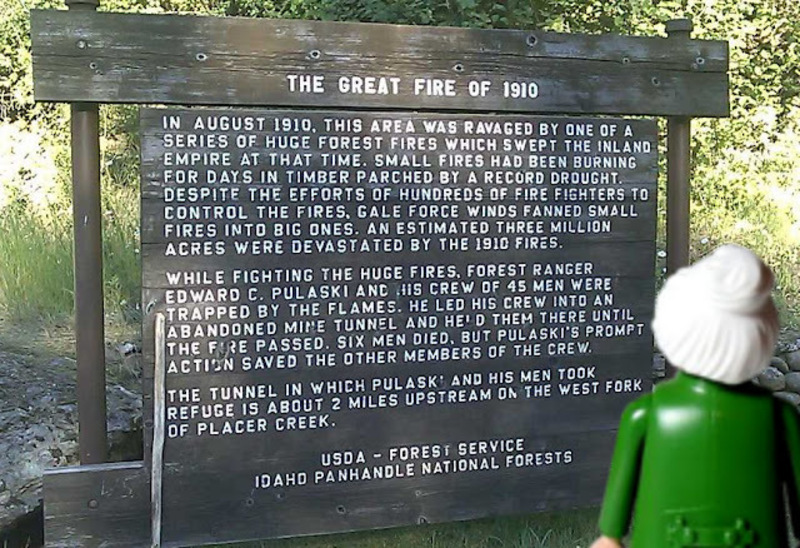

THE GREAT FIRE OF 1910 MARKER

The marker commemorates the "Big Blowup," a series of fires that burned three million acres. It specifically honors Edward Pulaski, who saved 45 men by leading them into an abandoned mine tunnel near this site.

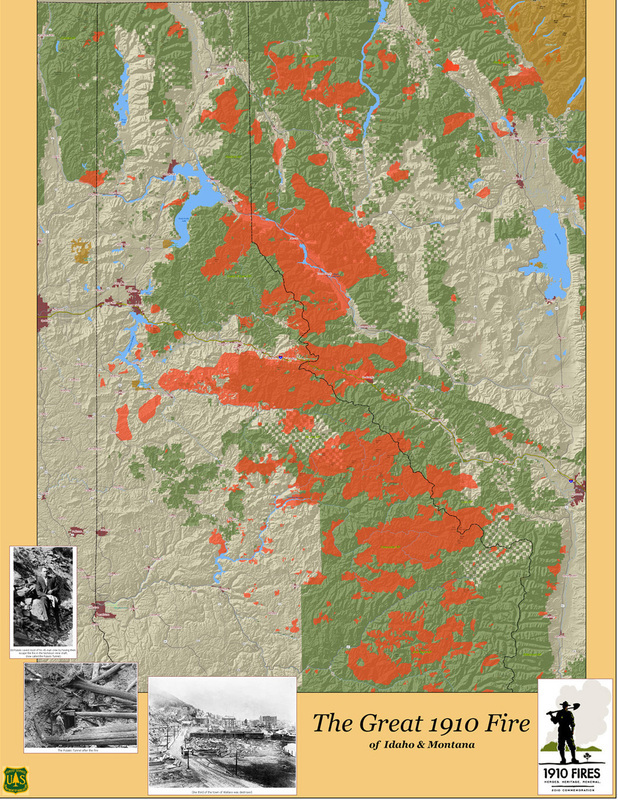

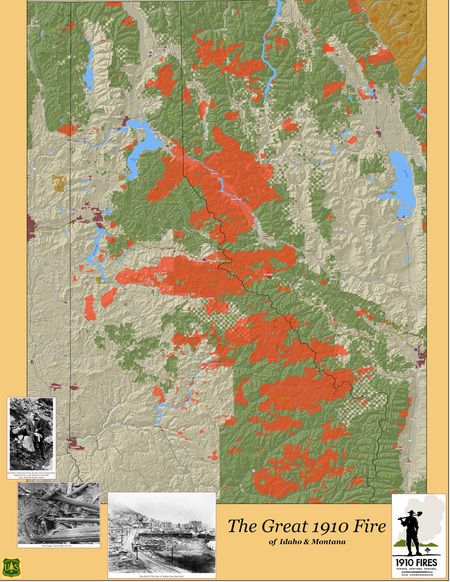

The Great 1910 Fire of Idaho & Montana

The Great Fire of 1910 burned over three million acres and killed at least 85 people. It established the U.S. Forest Service's primary mission as one of aggressive fire suppression, a policy that shaped federal land management for a century. The disaster also directly led to the passage of the 1911 Weeks Act, pushing federal-state cooperation in fire protection.

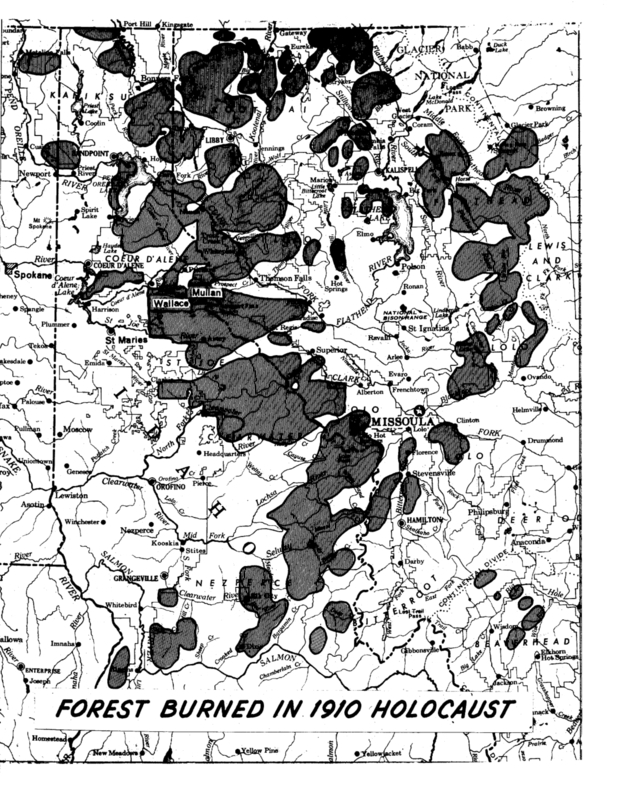

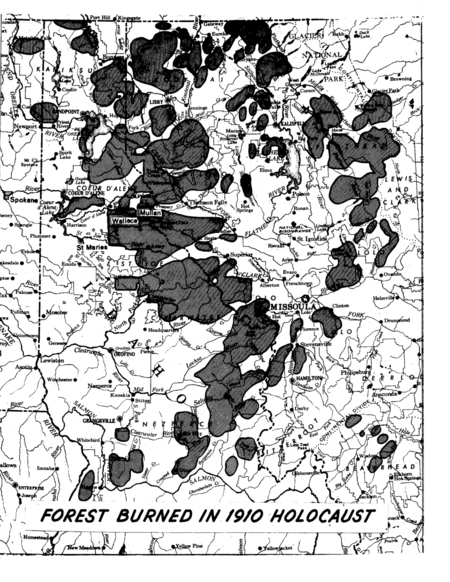

FOREST BURNED IN 1910 HOLOCAUST

Map produced by the U.S. Forest Service shortly after the 1910 fires, illustrating the massive acreage burned.

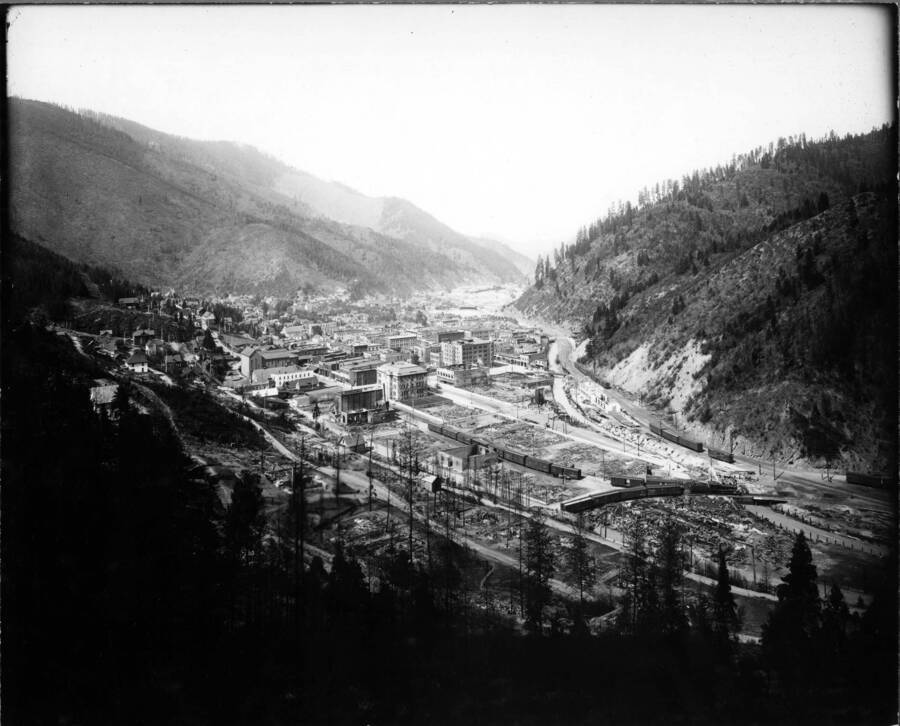

Forest Fire Aftermath, 1910 - Wallace, elevated view of town [02]

This photograph documents the aftermath of the 1910 Big Burn on Wallace, Idaho, showing how the fire destroyed nearly a third of the town.