Chestnut Collective

Collecting Stories Entangled with the American Chestnut

About the Chestnut Collection

The main, overarching question driving the entire investigation is trying to uncover the sociocultural and sociopolitical implications of the Chestnut Blight and subsequent loss of the American Chestnut on Appalachian families and communities. This question will be explored in all three chapters but especially chapter two (describing the changes starting in the past up to the present). To support and fully answer the main overarching question, I have identified secondary questions to be more precise and focused in my data collection and analysis. The first will be identifying the historical relationships and representations between the American Chestnut and people in Appalachia, which forms the focus of chapter one (past relationships). Lastly, in chapter three (present), I hope to represent what human-plant ecological assemblages are currently emerging from the blight infected habitats/remnant saplings as well as what is filling the American Chestnut’s sociocultural gap in Appalachian communities as it was disappearing.

Land Recognition

While land acknowledgements and recognitions are limited and only a starting point, we find it vitally imporntat to foreground how the fieldwork for the project was carried out on Shawnee, Yuchi, and Cherokee lands that were stolen from colonisers through mass genocide and force. Through the following research with the Chestnut, I would like to acknowledge these ways of living with the land, animals, plants, and fungi. As a white researcher on this stolen land, I am deeply committed to advocating for the rights to indigenous groups in the United States through radical action and activism fighting for expanded environmental justice reform.

History

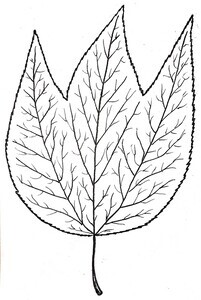

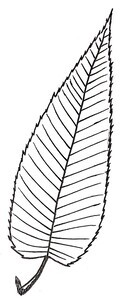

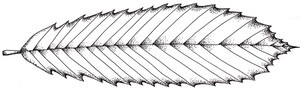

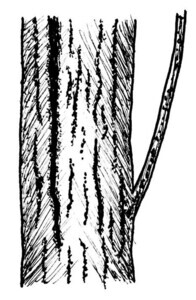

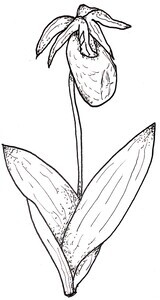

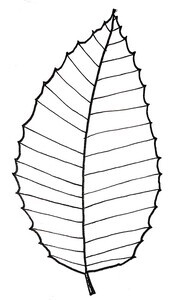

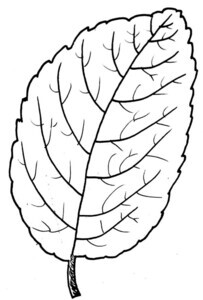

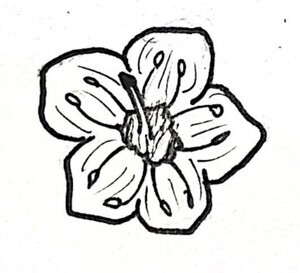

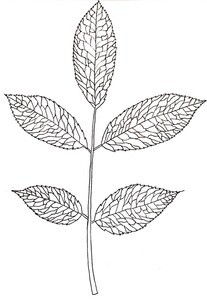

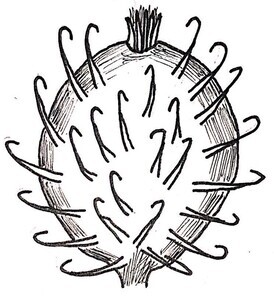

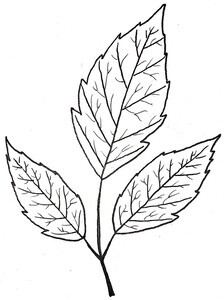

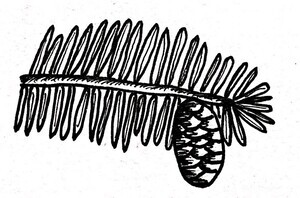

In the range of the Appalachian Mountains resides a multispecies community of unimaginable complexity. When standing in the presence of giant tulip poplars and hemlocks deep in the forests of Appalachia, there may be a feeling of wholeness. However, the tale of the American Chestnut fractures this imaginary abruptly when listening to stories of the past. In 1904, the American Chestnut trees at the Bronx Zoo in New York City were dying and a peculiarity was noticed in the natural trends of life and death among the stands of Chestnuts.1 The American Chestnut tree–Castanea dentata (Marshall) Borkh.–used to tower over the smallest of Toads and tallest of Tupelos, but was devastated by the unintentional introduction of a fungus pathogen in the north tips of the tree’s range. What starts out as a small dusting of orangish powder, turns into an obliteration of the vascular tissues residing on the outer layers of the Chestnut trees. Cutting off all nutrient flow to the great reaches into the sky, individual Chestnuts succumb to the behavior of a fungus in which the species did not evolve with over the past millions of years in which made an extraordinary jump via human introduction from Japan to the eastern seaboard of the United States.2

Fungal Introduction & Spread

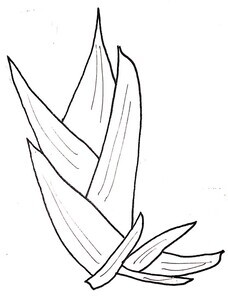

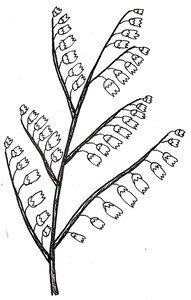

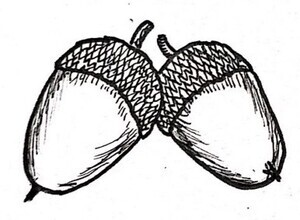

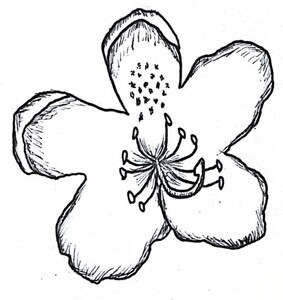

Starting in the early 1900’s and continuing to the middle of the 20th century, around 3.5 billion American Chestnut trees (estimates ranging from 95 to 99.9% of the native American Chestnut trees) died because of the human introduction of a deadly fungus: the Chestnut Blight–Cryphonectria parasitica (Murrill) M.E.Barr.3 The monolithic hardwood in which humans and animal species depended on greatly for nutritious nuts and rot-resistant wood is now considered functionally and ecologically extinct in the environment due to its inability to reach maturity.4 In the Appalachians, there are small American Chestnut saplings that are able to grow from the dead and decayed stumps of former giants, but the Blight kills them right before the age of flowering. This renders them able to exist physically in the world, but unable to sexually reproduce.

The Perfect Tree

The Chestnut Blight devoured as much of this ‘new’ Chestnut species that lacked the evolutionary protection its relatives, the Chinese and Japanese Chestnuts, had armed. The fungus species spread at rates of 50 miles a year and reached the southern foot of the American Chestnut’s range by the mid-20th century leaving behind three to four billion dead Chestnut trees.5 But the story of the American Chestnut and the Chestnut Blight becomes muddy and murky when other species are accounted for in the multispecies becomings–especially Homo sapiens L. The American Chestnut tree was regarded as the “perfect tree” among Appalachians living with the species over many centuries due to the nutritious nuts provided by the tree to wildlife (including humans), the rot-resistant wood, malleability in wood-working, and being one of the fastest growing species in forests.6 Many Appalachians depended on the tree to build homes and fences, feed their livestock and families, as well as serving as a source of income through nut and wood harvesting.7

The Lesser Majority

Many refer to the extinction of the American Chestnut tree as a ‘functional’ or ‘ecological’ extinction in which the tree can no longer ‘function’ in the ecosystem it evolved in and fulfill its former ‘ecological’ role.8 The portrayal aligns with many natural science accounts of extinction rendering the species to its resource and niche filling capacities,9 but here I will be moving more towards a multifaceted view of extinction. Extinction and the loss of species has occurred well before the Anthropocene, and will continue to the epochs after. What distinguishes extinction, specifically plant extinction in the Anthropocene from other eras like the Holocene and Pleistocene is what the focus of this work will be. The field of extinction studies has focused much attention on the charismatic megafauna of the world for various reasons (i.e. engage with public more easily, receive more conservation funds), but much less attention has been given to the “lesser majority” of species in the world.10 While I hope to not only focus on the megaflora of the world, I hope this piece cracks open the door of the “lesser majority” of species (i.e. fungi, insects, plants, bacteria, etc.) to the field of extinction studies. Having a better understanding of the human impact on the “lesser majority” is crucial of humans as we navigate through the Anthropocene.11 Through investigating Human-Chestnut relations, emotional political ecologies, and multispecies assemblages surrounding Human-Chestnut communities, I work to fill the deficit in the field of extinction studies.

Notes

-

Kuhlman, 1978 ↩

-

Hepting, 1974 ↩

-

Davis, 2021 ↩

-

Freinkel, 2007 ↩

-

Deacon, 2005 ↩

-

Rhoades and Park, 2001; Rhoades, 2007; Davis, 2021 ↩

-

Freinkel, 2009 ↩

-

Lovat, 2019; Collinge et al., 2008 ↩

-

Kane, Varner, and Saunders, 2019 ↩

-

Dourson and Dourson, 2019 ↩

-

Rose, van Dooren, and Chrulew, 2017; Rose, 2012; Rose and van Dooren 2011 ↩

Technical Credits - CollectionBuilder

This digital collection is built with CollectionBuilder, an open source framework for creating digital collection and exhibit websites that is developed by faculty librarians at the University of Idaho Library following the Lib-Static methodology.

Using the CollectionBuilder-CSV template and the static website generator Jekyll, this project creates an engaging interface to explore driven by metadata.