Sara Fitzsimmon Item Info

Topics:

Nick Koenig (NK):And then are you comfortable with me using your name? Or would you like to stay anonymous?

Sara Fitzsimmon (SF):No you can use my name.

NK:Okay, great. Okay, awesome. And then it's okay, if I use your affiliation or would you like to keep the Chestnut Foundation out of it?

SF:Nope, you can, I mean, that's a big reason why I knew all chestnuts so.

NK:I will say like full transparency. I'm not asking like any like, even though I'm saying politically ecologies, I’m not asking any like political questions. I'm just asking for your your beliefs. I think some people think I'm getting into politics, but I'm just really looking at the emotional feeling and changes and connection to chestnut.

SF:Yeah, okay.

NK:So I would love to hear like first like, your like background of like, where you grew up. And how you ended up to where you are trying to right now?

SF:Yeah, sure. And it's, it's about to start pouring. So I hope this doesn't hurt your audio or your ability to hear me.

NK:No, I can hear you. It's totally fine. No worries.

SF:All right.

So I grew up in Southern West Virginia in a town called Hanton, West Virginia, and spent the first 18 years of my life there. Spent a lot of time hiking, playing in creeks. My papa, I told you this in the email, my papa owned farm in, between Hanton and Beckley in Summers County. We still have a that as a family farm. And my earliest chestnut memory, I have two, you know, probably late, probably 10, 11, 12, I remember my granny collecting Chinese chestnuts from trees from up on the farm, out at the farm, but most of the farm and also at a camp that we have along the New River.

So my papa had planted Chinese chestnuts as part of the West Virginia Department of Agriculture's attempts to replace the American Chestnut. Now, I didn't know anything about the American Chestnut at that time, I just don't have now in retrospect know that, that's why I had those Chinese chestnuts on as farm and why he planting them out at camp those those trees are still there.

But granny would collect those Chinese chestnuts and I remember hearing crunchy from a bowl of chestnuts on the counter, which were weevils eating the nuts, and I will never forget that sound. And I'm like, Granny, why would you? Why would you eat that and she would just say ‘I just cut it away’ you know, she cuts away all the bad parts and throws the worms away and you just eat the chestnuts you know, regardless.

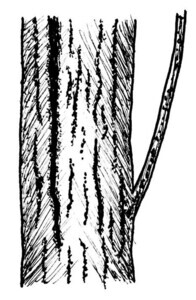

And that's one of my earliest memories of chestnuts themselves. And then my papa, who was a product of the Depression, he hoarded everything. And including, so he taught in one room schoolhouses and Summers County, before he became a superintendent of schools for the county later in his career. But through the 30s and 40s, he taught in one room schoolhouses. He wrote a book actually on the history of one room schoolhouses in Summers County. But as they were starting to tear down those old one room schoolhouses in the 80s 90s, and well, 80s and 90s. He died early in the 1000s. He would collect all the wood but primarily the chestnut that made up those one room schoolhouses.

And the house that I grew up in the basement was paneled. And some of that wormy chestnut that papa had salvaged from those old one room school houses. So I knew that as a story from him, it was a big part of his life. And he passed away before I could really sort of interrogate even more about his connection with the tree. I just knew that he, he had a big connection to it because of his farming upbringing, upbringing, and was really concerned about it. He loved the work that I was doing. His my work only overlapped about two years with him before he died. I just remember him being really excited and hoping that I would plant trees up on the farm when we got blight resistant trees. And that's, that's still my intention. My uncle Charlie still has that farm and we go up there regularly. So at some point in the near future, I want to plant you know, a nice little grove up there and his honor and for the family.

NK:Oh, that's amazing. Do you know which of the restored chestnut that you want to plant? Do you want to do like the transgenomic one or the backcross breed one?

SF:Well, because I'm doing both.

NK:Okay, gotcha, gotcha.

SF:And I have a direct line to get whatever material I want. Then I know my intention is, so the person who is in the car with me, he and I work at Penn State for the Chestnut Foundation and last year was the first year that we put transgenic pollen on our best backcross trees at the arboretum at Penn State. So we've got what's called stack resistance. We're going to test them this summer through a small stem assay and see if that if there really is increased resistance by adding the backcross in with the transgenic tree.

I have strong excuse me strong hope that that will that will be even better than the transgenic on its own or the backcross trees on its own. So that's ultimately what I'd like to plant it down there is stuff that we ended up making and that turns out really good. You know, we have some really good backcross trees. If if the transgenic doesn't get deregulated, and I'm more than happy to plant, you know, the backcross stuff that we've been making, we have some really nice selections that I, I wouldn't mind playing down there at all.

NK:Gotcha. One of the questions I've been asking people is, to what extent do you want to see people planting the restored chestnut? As in on a very small scale in their front yards, or do you want? Would you like to see personally, people going out into the forest and planting it and restoring it? Or where do you fall on?

SF:All of it, all of it. Uh, you know, my previous title, I was recently promoted and given a new title, but my previous title was director of restoration. And even in my new role, I still think about restoration a lot to think about, how's this gonna get back out in the woods? And people say, Sara, what should we play in the gaps? Should we plan just to your question, like small little plantings and backyards or planting big plantings of 1000 trees? Should they be monoculture. Should they be interplanted with oaks? Should they be planted on strip mine lands or replanted in old fields? Or should you, you know, take a terrible site that's like covered in low value timber and strip it and, and put on Chestnut? And I say, yes, all of that. Because the reintroduction of a species across millions of acres is going to take all of that to happen. It's going to take decades, it's going to take millions 10s of millions to hundreds of millions of trees. And you can't do that by by being picky. You know. So really, it's going to take everybody employing every method that they can to get as many trees out there. And I mean, I think what you're talking about priority is going to be well, we're staff priority is going to be and I think that that's a difference.

But you know, people and what they're going to do, I want them to do all of it. Because it really is going to take everybody getting everything they can to get these things out in the landscape on a landscape scale.

NK:Have you been have you personally been met with resistance from people about the hybridity or the kind of just I was talking to Rex Mann, and he was saying the phrase playing God is what some people have said, but have you personally been met with any resistance similar to that?

SF:Yeah, on both ends, so people, people don't like Chinese chestnuts involved in their American chestnuts. There's this sort of inaccurate sense of, of purity of species like I, while I agree that we should have a native tree as native as possible, there's a lot of ecological reasons for that. I'm not against hybridizing, as long as you can keep the ecosystem services that a given species can impart. So I'm not a purist. But but there are people out there who are absolute purists like I want nothing but a pure American, just not. And so they don't want any Chinese in it.

The real high level purists don't even want to a trans gene in it. And then of course, you have the folks who are very anti GMO. And, and all of them have their reasons I don't personally agree with them. You know, my my goal, my philosophy is, as long as what I want is a tree that restores ecosystem and economic services that the species once did and whatever does that let's let's do it.

NK:Gotcha. When you were talking about the first memories of like chestnut, what was, was there any like stories that your father your grandfather, your grandmother mother told you about like the chestnut when it was it? It's like heyday per se?

SF:Unfortunately, no, no, we never. That was never something that we really talked about. I do remember when I so after I've been working couple years, my papa had already passed. My granny was deep into dementia. Going back home and talking to some other local folks who have since passed away too. But it is interesting once you start talking to people, especially in it where I think, I think it was like deep Appalachia like southwestern Virginia, western North Carolina, eastern Kentucky, Southern West Virginia, like people have really deep connections or had deep connections to the tree and the land and the American Chestnut in particular.

So I would hear a lot of the stories on echoed, like being able to take five gallon buckets and just fill them with one scoop, you know, at a time when when the chestnut was at a its height or people let you know the livestock loose into the woods, and feeding the like I had read all of that. And some of the historical literature. And some of the people, the old timers I talked to would echo those same stories, you know, none of which I recorded or documented, but it was just interesting to hear them from firsthand accounts. The person who is so unfortunately, not my papa or granny, or even my, my own father, who's not very outdoorsy.

He did a really full accounting of, and I'll ask him tomorrow, and you're still doing interviews. He got some really great first person accounts of people who are alive and when the blight hit Indiana, which was a little later than like West Virginia or Kentucky, and the way that they sustained their livelihoods was because of the the loss of chestnut. And that was a really interesting perspective that I had not heard. Indiana is the only place where I've heard it where, because the chestnut was dying, people were able to subsist economically very hard times, because they were able to sell the wood, or sell the nuts, as that species was was starting to get wiped out.

NK:I hadn't come across that in the literature anywhere. That's really interesting. And I think like, I share the sentiments you do, like I've heard, I've heard these, like, firsthand accounts. And I think that's like, what kicked me off wanting to do these interviews is because of.

SF:Yeah.

NK:Just like how profound it was. I guess, like that leads to like, another question I've been asking people was like, Why do you care about it? Kind of at a very, like, elementary level of like, what is driving your passion and care for the chestnut? If that's what you do have?

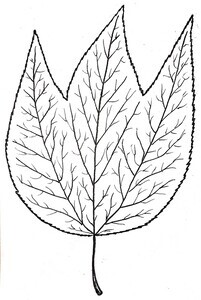

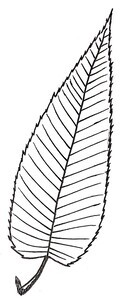

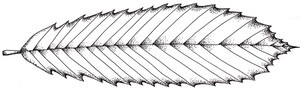

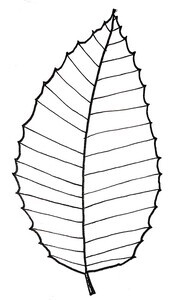

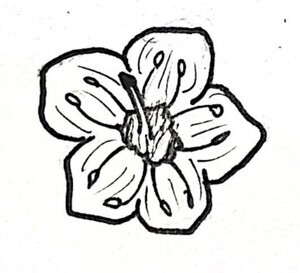

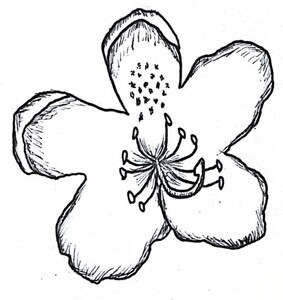

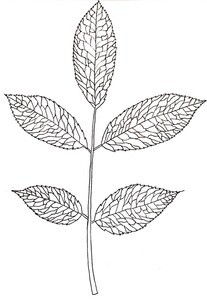

SF:Yeah, I think I do, mine is the people. I mean, of course, I care about the ecology and the tree itself. And I really enjoy the work that I do like working with tree. There's something very charismatic about it, and I can't explain it other than like, it's a beautiful leaf, like it's very aesthetically pleasing, it grows really fast. It's a fighter, you know, just for this thing to hang on for so long after so many assaults. And just keep going. It just it wants to be rescued. You know, and, but the thing that drives me day to day and like gives me energy are the other people who feel the same way.

It's a really amazing community. And I love the people that I work with and share. Like, I'm so, Troy and I are going out to Indiana, we're staying with the Indiana President, Glen Cotinick, he's he's cooking us a delicious dinner tonight. Traveling around Indiana with us meeting other people who are like is growing just nuts with the Savannah Institute up in Wisconsin, and we're gonna see this amazing, naturally regenerating stand up in Wisconsin. I mean, it's just like the stories of people like all their work intersecting. It's not it isn't just one person or one lab or one group. It's just all these people with all these different types of work and approaches and strategies. And we all have to work together to bring the species back. That's that's what I find really inspiring and energizing.

NK:And this is like going into like, your professional career a lot has it.

SF:I mean, that's, that's what I do. I've been working on a single species woman I've been working on just on since I did my masters work on it in 2000, and hired on full time in 2003. And that's all I've done for basically my entire career with the exception of a small amount of time working for a beer magazine and working at Kroger. I've worked on Chestnut not my entire career.

NK:Gotcha, yeah.

I think that's like really different than a lot of the people I've talked to a lot of them are retired or they're up and coming young. But that's really awesome to hear that, has did the like chestnut like changed your perception of the outdoors, or Appalachian?

SF:I tell you what, it's probably not Chestnut specifically, but because the species that I've worked on about tree breeding has made me much more patient. Because it just requires time requires time to grow trees to make trees it takes them a long time to flower and I mean there are techniques to reduce the amount of time for all of those things but it's still a lot easier or a lot harder to work with and say Arabidopsis or tomatoes or corn, you know, and so tree breeding in general has taught me a lot of patience.

I can't go into the woods without looking for chestnuts. And that's when I first moved to State College to Penn State started working there, I joined the caving club. And one of the main reasons that I that I went to cave was because I could rest there in a in a sort of outdoor activity, not outdoors, but you know what I mean? Like not because there's no chestnuts underground. So I wasn't, I didn't feel like I was at work. And I've made peace with that though. I've made peace. And if I'm out hiking, like I know, I'm gonna look for trees. I can I can do that without feeling any anxiety or feeling like I have to document every tree that I find.

It's every now and then it's like, oh, I got to something to get that. Gotta get that tree. I got to stop. Oh, look at that tree, you know? Yeah, every little bit. I’ll still stop and get that I think that's the major thing is that, like, I'm just always looking for them. And just trying to, when I look at the woods. I'm like, you know, what's the eco type is this? Is this going to be appropriate for chesnut planting? Like, what does this mean for restoration in general? Like? Yeah, that's, I definitely have a new perspective. Because of what I do.

NK:Yeah. I feel that with, like, studying botany and like, kind of the green curtain being pulled out from my eyes.

SF:Yeah.

NK:Like always ID’ing the plants. What caused you to have that like transition between? Like feeling anxious if that's correct to like, coming to peace with it? You said?

SF:I think it's just because you you reach a point where do you know, you you there, you have no other choice. You can't control that, right. I mean, and I love like being I love being out in the woods. I love camping. Like I can either be anxious all the time and say that it sucks, or I can just embrace it and deal with it. And you know, that's what some time and some maturity and realizing that, especially like, around where I live, there's Chestnuts all over the place.

Walking my daughter to school up the hill. There's at least 500 chestnuts on that little hill. And I haven't documented them. Yes, I could. And I'm like, oh, I should get up there one day and, you know, document them, measure them and put them a tree snap or like map them. You know, I'm okay that I haven't done that. I think maybe I will one day, like if I lived much more on the outskirts where they are much more rare. Like when I come out here to Indiana, it's a lot harder to find them. And that's, that's a place and a time when I feel much more driven to document anything that I find I look more consciously for trees. But where I live, luckily, they're they're a dime a dozen. I can, I can give it up.

NK:I've asked people to like kind of give their own list of like the plant species and habitat is like perfect Chestnut, in their opinion. So what would you describe like the perfect chestnut habitat? Where you see it, where you kind of see it occur? And what other plant species or like soil types or elevation? Do you find that the most?

SF:It's not fair, I guess, because I've done a lot of habitat modeling.

NK:Yeah, yeah.

SF:So well drained, sandy soils. I mean, what's really interesting is seeing trees and like, for example, Sandy Hook, New Jersey, or in Michigan, or even actually behind my house and what's called the Scotia Barrens, where I see tons of trees, you bend over and you pull up the soil, and it's just almost pure sands. And so, based on our habitat modeling, you know, that sand limit, there's a lower limit, so they don't like any less than 25% sand. And there's actually an upper limit, they don't like any more than 75% sand at that point, there's not enough water holding capacity, and they can't survive.

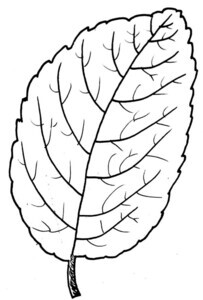

And we see that in defined areas. For example, in southern New Jersey, it's just too Sandy there. But low pH well drained sandy, other species that tend to be much more inclined White Pine, Blueberry, your ericaceous species Azalea, Mountain Laurel, Rhododendron, Chestnut Oak, Hemlock, in some cases. Yeah those are the most often ones that I see in parallel.

NK:Gotcha. Yeah. That's it's very similar to what a lot of people told me.

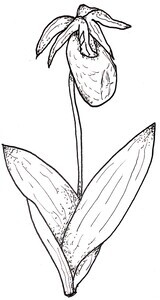

SF:I will say, it's one of the one of the most lovely times to go hiking is sure about now or like a week or two before now when you go out and you see all the spring ephemerals and you see like all, the pink lady slippers and trout lilies and things coming out and similar types of areas, but those aren't as noticeable year round.

NK:I don't know if you've seen this, I just saw it the other day but I saw chestnut it's almost dead because of the blight, but it's like a maybe like four or five inches in diameter. But it had a buffalo nut sapling growing next to it.

SF:Oh really! Okay.

NK:Which I'd never seen growing with, but I because they're like hemi-parasitic. I thought about like, how it could be parasitizing off the Chestnut sapling.

SF:Yeah!

NK:Which was super funny.

SF:Double parasite.

NK:Yeah

I felt bad for the Chestnut. And I was like, it's already, like going through a lot, you know.

SF:Right.

NK:So another question I have is, would you like say that, like, Chestnut became more a part of your identity? Or has it always been a part of your identity? Or how's that, like, potentially become if it's not a part of your identity? What is it a part of a part of your life?

SF:I mean it wasn't always, I would say it went from music and outdoors to I mean, I've always had a love of the outdoors. And then I started following what I've, I've always loved Duke basketball. Then I went to Duke and I became an absolutely rabid fan of Duke basketball. And then, you know, I started my career. And then I had kids. And so now it's funny you go through my phone and what I have pictures off it's like Kid kid tree tree tree kid kid tree tree kid tree. And that's like all it is. So that's that's kind of where I'm at right now in my life.

Do your, do your kids have a passion for the chestnut or?

Um, kind of, I mean, they still so they're young. They're five and seven. So they still don't hate it entirely when I take them to the greenhouse. Come on, kids, let's go water the trees you're like, okay, because they can run around. And Parker, my daughter is actually in the last magazine with the chestnut magazine. She came up on a trip with me to Erie, Pennsylvania. And so there's a picture of her and one of the LSAs near Erie. And actually, this past week, they went with me to New York, and we dropped off a bunch of trees and they love going to New York because they love New York Park hot dogs. So I'm like, Come on kids. Let's go, you know, do do these dog and ponies. And I'll get your dog in New York and like, okay, so I don't know if it's so much they love the tree. They just kind of like hanging out with mom. And I'm sure one day that'll change. But for now, it's that they're okay with it.

NK:Gotcha. Um, did you have any other pieces of Chestnut growing up? Or do you have like Chesnut in your house? Kind of as a product that you use or?

SF:Yeah, so because, well I have a lot of that wormy chestnut from from my house, my childhood home, we sold and moved into another home in town that was that we inherited. And before we moved, my dad pulled all the wormy chestnut from the basement. And we took that with us. So I still have some boards from the house.

Oh, that was a big ol rock that I don't think broke our windshield will say good thing. Good thing. It's a rental. So, so I still have a couple of those boards with the wormy chestnut that my papa had taken out from from the one room schoolhouses. That was in our basement. One of our members actually wasn't a member. He's a he was a woodworker in West Virginia. He then made a really, really nice walking stick out of some of those boards. That turned out great. And then when I got married to my husband, people showered us with lots of Chestnut stuff's rather beautiful, Chestnut table. I've got Chestnut bowls, I've got Chestnut frames. There was actually a really nice set of postal stamps that came out about 10 or 12 years ago, got feature chest on as part of like the Eastern Appalachian woody ecosystem, and there's a blighted cesta in front of that scene. And so my dad got a bunch of those and then had him framed and wormy chestnut frames. And so that's hanging up in the house. I got a whole bunch of chestnut stuff in my office, of course. So Oh, and a friend of mine got me like a set of glasses that have etched chestnut flowers and leaves on them. So yeah, it features not as prominently as or it features a little more prominently than I would like but I mean, what are you going to do? I got just the earrings I got I got all kinds of stuff.

NK:Do you have a favorite piece?

SF:You know, it's really hard to choose now that you're asking. I think the most sentimental would be my my father's passed away too. So I would say you know that frame and Chestnut stamp just because you know, that was something that he put together and he was very proud of the work that I do. I love the walking stick because it looks really cool. And it was made by an awesome woodworker in West Virginia. The table is beautifully made. It's a really spectacular piece. So you know, each one of them have a great story that means a lot to me. But yeah, probably the framed stamps because it's from my dad.

NK:Thank you for sharing that. That's really awesome. What one of the questions I have, and this is like, kind of, I haven't been able to find in the literature, and I was wondering if you know, do you know how long the roots can live and produce the stump or the little saplings out of, and like how long?

SF:I don’t, we don't know that. So from what I understand the root systems as long as they can be released over and over again, and they get enough sunlight, and the deer don't eat them all to hack, or they don't get made it to a Home Depot, like as happens in some places. That's true story. Then, then they can persist indefinitely, from what I understand. As long as they can get released and throw up new sprouts. Whenever they throw up the sprouts. They create new root systems that that can then that are no no longer exhausted. So like the old root systems are probably long gone, what they've done is created new roots on top of those old ones. But if those suppressed sprouts don't have access to enough sunlight, or the deer keep eating them back they're not regrowing more robust root systems, and then they get exhausted. So I think the answer is more resource-related than time.

NK:Okay, gotcha. I've been like people have asked me and I like, have no clue what to say. I say, I don't think anybody really knows. Because we haven't had enough time to figure that out. But yeah,

SF:I think I think it's resource limited.

- Title:

- Sara Fitzsimmon

- Creator:

- Koenig, Nick

- Date Created:

- 2022

- Description:

- Interview with Sara Fitzsimmon

- Location:

- Eastern Kentucky University

- Latitude:

- 37.73823073

- Longitude:

- -84.29690252

- Type:

- record

- Format:

- compound_object

- Preferred Citation:

- "Sara Fitzsimmon", Chestnut Collective, Nick Koenig

- Reference Link:

- /chestnutcollective/items/chestnut051.html