Contents

Chestnut050

Nick Koenig (NK): I'll I told you about the project first, I was in the, I'm gonna be transparent in this. So in our study, we're just looking at questions of human environment relations. And they were like, just like started digging, tell a story that hasn't been told. Try to tell it with people. And I was like, okay. Oh my god, like, everybody talks about extinction. But nobody talks about plant extinction, or like the lesser majority.

Savannah Clark (SC): Yeah.

NK: And I was like, Okay, I want to, I want to learn more about this. So then, I've been interviewing people who are Appalachian or grew up in Appalachia and then who have some ties to the Chestnut whether that be from childhood, whether that be from recent years. Talk to people everywhere in between.

SC: Have you got a lot of stories from people that like...

NK: Old timers?

SC: Old timers

NK: Yeah.

SC: Oh, so cool what they remember of the Chestnuts

NK: So feel free to just tell me what you want to tell. Don't tell me stuff that you think I want to hear. Just tell me exactly what you feel or what you don't feel about it. But the first few questions are just like, like a background where you grew up and where you're from?

SC: Well, I grew up in Bath County, Kentucky, which is kind of like in the foothills of Appalachia, really close to Cave Run Lake and a lot of the community there is super like it's just, they love to forest, everyone it's that's part of the community in Bath County is like getting out and going to forest, going hunting, having a good time and enjoying it. But I feel like a lot of the community doesn't realize the, the conservation effort and stuff that goes into it. And that's what really drove me to go into conservation work and start like, helping out with the forests and stuff. And like, because I wanted to spread that knowledge and Bath County in general, I don't know about Chestnuts there, like I don't have I have never dug deep into like the history of Chestnuts in Bath County, but I'm sure they were there.

SC: Just a lot. Yeah. Foothills of Appalachia, a lot of country, a lot of us are country, you know, old timers have those big stories. And...

NK: I know like, imagine, I don't know you, you know

SC: Okay,

NK: Because I know some of the stories you've told me, you know, act like you never told them to me, but what did you do, like growing up? Like day to day, if you were outside of school?

SC: So, I guess. Yeah. So like, let's, let's say this summer. So I'm, in the summers, it was a lot of times I spent my time, most of my days with my nanny and my papaw at their farm back in Sharpsburg. And they, we were always just going outside and playing ,me and my brother having a good time. And they had this little plot of forest that was like right back on the corner of their property. And we always go back there, climb the trees, and just kind of explore around and see what we could find.

SC: And it was just so like, great to be in the forest and like getting away from everything. So the forest was super, such a, such a special place and it all like inspired that curiosity in me because I wanted to find out like where, like what everything was and like what it did, and like how it played into the ecosystem. And it was just so, so fun getting to go out in the forest and learn about all that stuff.

NK: Did you know you wanted to study bio in high school?

SC: No. In high school I wanted to, I wanted be a doctor.

NK: Oh really.

SC: I wanted to go and be a dermatologist. And, but that time I was more, I was very, like, I don't like saying it. But I was very money hungry, at that time. I was like, Yeah, I want to get a good paying job that I can take care of myself and my entire family. But then I slowly realized, like through college like I would be miserable doing that. So I want to do something that I actually enjoy. And that's what really like when I took my first botany course, that brought me back to that curiosity that I had as a child.

SC: And I was like, this is it. Like I want to go into forestry and like botany and studying management and ecology now and figuring all that, figuring out those questions out that I had as a child and like actually learning in depth answers to them. So that's what drove me into forestry.

NK: Did you learn about the Chestnuts in the botany class?

SC: So yeah, that was the first time like I actually truly learn about like what happened to the American chestnuts. Because it wasn't like, I talked about in community, like there, everyone had Chestnut, pieces of Chestnut furniture that were like super valuable. And all this. I never really knew why they were valuable until I found out about the blight and like the extinction of the chestnut.

SC: And through that, like once I started learning about the Chestnut, I was like, Oh, I really want to work like, work with this some. And that's when I started working with the American Chestnut Foundation, out of the orchards and stuff. During their workdays, I got to help them out with the Kentucky State Fair, doing like just a little info booth with them. And that was so fun.

NK: What did you do there?

SC: So they had like a little Plinko game setup. Yeah, with Chestnuts and they would drop them and drop them in and they get a prize of it when in the right thing. And like, I was just kind of like informing everyone just like, Hey, do you know that we used to have like trees as big as the Redwoods in the East Coast. And like, we can have that again. And just trying to get kids excited to learn about Chestnuts that was like my thing there.

Nk: Why? Why did you want to get kids excited?

SC: Because kids, they're the next generation. They're the ones that are going to carry on our efforts that we can like that we are working on now. Like, if we don't inspire that curiosity and love of nature and stewardship in them, then we're not gonna, then all of our work now is pointless. So if we don't, we gotta like, it's on the next generation to continue this on. So it's has to have to have to have them inspired.

NK: You said furniture was Chesnut, do you have some here?

SC: So I don't have any of my apartment. But I have a piece that my nanny gave to me from my grandma Clark. She got it from her father. Yeah, her father, trying to remember the story that, her father got it from a carpenter that lived over in Brown County. And he she bought it for I think was like 10 bucks at the time. And then my nanny, she actually put it out in a yard sale one year and was trying to sell it for like 400, 500 bucks, because it was Chestnut.

SC: No, no one, no one in Bath County had the money to spend on $400, $500 on it. a chestnut wardrobe, so she just passed it down to me. And like, I'm so grateful that she kept it because it's just so so beautiful. And like, such a it's like a piece of history too, because it's got all that, that that wood from those trees. And it's kind of inspiring, like we could have this, like not necessarily the furniture, well, we could have like the wood and bring back that culture that went around the American Chestnut, if we brought the chestnuts back

SC: Because I mean, Chestnut hunting, and then the chestnut logging, like, it was all such a huge important part of the community and the culture of Appalachia. And then now it's just gone. And I feel like bringing it back would be like a collective, I don't know, it would be good for the collective and like bringing everyone together and bringing back some of that tradition because I feel like Appalachia has a loss a lot of that, like, we've kind of become separated from each other in a way but I feel like the Chestnut could bring could bring some people together. Obviously, it's not gonna bring everyone together. Bring a lot of people together, especially like in the woodworking communities and people collecting chestnuts to roast and all that stuff.

NK: Have you ever eaten a Chestnut?

SC: No, I actually haven't. I've had like, I've tried like a Chinese chestnut, but never a true American chestnut.

NK: Bu you have eaten a Chinese Chestnut

SC: Yeah.

NK: I've never, I've never eaten them.

SC: They're, they're good. It's like soft and crunchy at the same time. I don't know how to describe it. Like when they're roasted. It's so good. And nutty.

NK: I think you'd be able to get some from saplings

SC: Yeah, that's what I was telling my mom. I was like, Yeah, you guys like I'll go out there and do the hand pollinating for you guys. And you guys can collect them and we can roast them for Christmas.

NK: What do you think is like a part of like an Appalachian identity, kind of those core values to you?

SC: The core values of Appalachia? Family. That is number one, I think family above, is above everything else in Appalachia, because without that strong family bond, you're not going to survive in a lot of these areas like you have to have that connection and like there's people around you to help get you going and also family like that's, that's your roots right there.

SC: And that's what shapes you and develops you into the human you are and Appalachia it's a family. Community to a sense, because, there's a if you go through a lot of like Eastern Kentucky towns, they're gonna have like fish fries, like someone's house burns down, they're gonna put it there. The whole community is going to come together to support that person and make sure that they have what they need.

NK: Did that happen to anyone you knew growing up?

SC: Yeah, so, one of my best friends in high school, her name CD, and she, her house burned down. And we everyone came together for whole high school and we did a fundraiser for her to get, help them find a new place. Get her. It was so great. We like everyone collectively in the high school got her a bunch of art supplies, but she was an artist and helped her get her like she was able to save a couple of her paintings. And it's so amazing because like she is gone so far in her art now and it's like the community didn't come together to support her and get her back on her feet. Like who knows where she would be like she is doing big things in the world right now.

NK: Do you remember when you first ever like heard of Chestnut? The first encounter?

SC: It was probably like talking about like, like furniture and stuff earlier as like when I was a kid I never really like truly understood like how big and massive and important these trees were until I got into college.

NK: What type of furniture was it?

SC: So I had a, I have a wardrobe.

NK: The Chestnut wardrobe.

SC: And then my nanny's also got no she sold it, but it was a coffee table that was made out of Chestnut. And then I think that's all the pieces of furniture that she had. And then my mamaw, my mamaw, Annie, she's got a dresser just like a normal dresser. I'm trying to think if anyone else I know, furniture. That's all I can think of right now.

NK: Did you did, have you ever talked to any old timers about Chestnut about when they used to see the chestnut trees or anything?

SC: So no, but like, that is something I want to do. Like I want to get back and like back into community in my community and Bath county now a lot more involved in it. And learning about how, like what Bath county looked like before it was really developed. Because throughout my life so much of the county has been expanded into and like, like we used to have like right off of the exit there used to be a big forest like right, not like a big forest, but you know, like secondary succession, that kind of area.

SC: And they just cut it all down to build a trailer park and a Save-A-Lot. And I'm like, Yeah, I guess we needed the housing and stuff. But there's so many areas that were already cut and like big fields and like old farmland that we could just reuse and repurpose into something else but...

NK: What kind of like feelings does the Chestnut give you? That's kind of a broad question. When you've worked with the Chestnut?

SC: Hm, I'm trying to think of how to describe it.

NK: Like when you're working out at the orchard or kind of the encounters maybe with the furniture?

SC: Hopeful honestly, because it's really hopeful, inspired. Because seeing all these people work together so hard on, just for just this one tree, this one species of tree. And if we could take that collective effort like that collective effort to for one to reimagine what would you do for everything? And like for the whole forest, and it's just getting that attitude expanded I think. Hopeful inspired.

NK: Why should ,Why do you care about the Chestnut? Or why do you, why do you spend time with it and volunteer?

SC: I mean, I love trees. That's first and foremost. I just love trees, like there's something, something about them that just brings me so much joy and like I just look at a tree and I'm like, this is what allowed us to come up and like did like, allowed us humans to evolve and like just to get here but without. They just filled me with joy. Honestly, every time I look at a tree, I'm just like, Yes, this is, this is what I'm meant to be doing meant to be protecting.

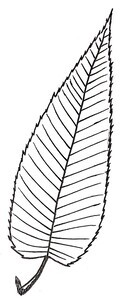

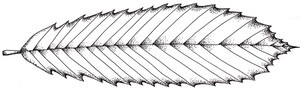

SC: And the Chestnut it's super. I care about it because like imagine, just imagine like we had these massive trees out here like the redwoods because I've seen them and like and it was so ecologically important, like, Isn't one in every three trees previously was American Chestnut like to have that out here, again, these massive beautiful forests that have this incredible canopy that could support an entire different level of life that we had.

SC: And I don't know just having that, that diversity, magicalness back in the forest would be so so beautiful, amazing, I just, every, all the good stuff, it would be so great.

SC: And like I said, I think having the Chestnuts back to would help kind of bring a little bit of a sense of community back as well, because like so many people can like, think that to cut down one chestnut tree, that you can't do that with one person. Like, it's going to take a multiple, it's going to take a whole group of people to bring that tree down.

SC: And then the people that have to work with the wood and then build it into something and then people coming out and collecting Chestnuts as a family before Christmas to roast them. And they just it's just a lot like community, beauty, inspiration, yeah.

NK: So in terms of like the restoration efforts, what extent do you think it should be restored? Or should it be restored? Or how would you like to see it restored in Appalachia? Yeah, how would you like to be see it restored in Appalachia? If, if you want to see it restored?

SC: Well, I definitely want to see it restored in Appalachia, how though? I feel like incrementally doing it, like saying, because right now we're at a point where we don't have Chestnuts that are completely blight resistant. So getting those into areas and finding out like which ones which areas it's going to be, like, thrive in the most while it's in these early stages. And then moving on to wider areas and actually, and like letting the Chestnut spread itself.

SC: And like not really forcing the reintroduce it and reintroduction to it but like going in maybe to our public lands, starting there and introducing it and then slowly having like community programs, where we could be like, Hey, we have this, like we have Chestnuts here that we can give you and help you like reintroduce them onto your land. And here's the benefits of all the chestnuts and like getting people slowly to kind of introduce those on farmlands and the places that they were before.

NK: Do you have any like, thoughts on on, do you have thoughts on either the hybrid or the transgenomic one specifically?

SC: So the hybrid one is the one they are actually cross pollinating.

NK: Yeah

SC: Okay.

NK: And then transgenomic one is the gene.

SC: They're actually going in selecting the blight resistant gene and entering it?

NK: If you don't have any thoughts on it, then...

SC: I yeah, I don't have an opinion on that one. Because I haven't looked that deep into like the difference in those efforts, in the efforts. I just know that. I mean, whichever one I think makes the most like, gives the tree the Blight resistance but keeps the most of the genetic integrity of the actual American chestnut. Because I feel like once you get to a certain point with crossing them, we're going to have a whole new species. And so technically wouldn't be an American chestnut. But then again, species identification, that's just that's, that's just that's a human thing that we've, we've come up with, but because every, every plant is going to have some genetic, genetic difference. It's just finding when is that genetic difference to go into a new species?

NK: Would you plant Chestnuts on your property, if you could?

SC: Oh, hell yeah, I mean, um, of course, I've got the ones in the office. I've called, I called my nanny, I was like nanny, can I put a chestnut in your yard? She's like, Yep, I was like Mom can I put a Chesntut in your yard? She was like, Yep. And I like, Dad, Chesnut in your yard? And he was like okay. And like everywhere, Chestnuts everywhere I can plant them and spread them as far as I can. I really hope that I can get on that land, the 30 acres that we have back there so that I can plan a bunch out there.

NK: Do you have anything else you'd like to add? Chestnut stories, storytelling. Anything in general

SC: I don't think I have any stories. I mean, whenever I was at the State Fair doing that work, the American Chestnut Foundation, it was just, the wonder on kids faces when you're like, we could have trees as big as like, huge trees, as big as redwoods out here. And they're just wow. Like, we really had those one time. And I'm like, Yeah, we could have them again. And just, I think that emphasis on informing the next generation and getting them inspired to continue the efforts and realize that we can have these back. It's potential, like if we if we just continue working on it. Like that's, that's my driving, drive drive home point.

NK: Okay, I have one follow up question to that.

SC: Okay.

NK: When you say informing next generation, is there a reason that you so deeply emphasized, next generation? Is it a tie to the future or tie to the forest or a tie to religion or to the youth?

SC: It's a tie to prosperity, I would say, because, like I said before, kind of all of our work now is pointless. If we don't continue like continue , make sure that next generation has that information to continue our work, and continue the stewardship of the forest.

NK: Thank you, Savannah.

SC: Yes.

Chestnut051

Nick Koenig (NK): And then are you comfortable with me using your name? Or would you like to stay anonymous?

Sara Fitzsimmon (SF): No you can use my name.

NK: Okay, great. Okay, awesome. And then it's okay, if I use your affiliation or would you like to keep the Chestnut Foundation out of it?

SF: Nope, you can, I mean, that's a big reason why I knew all chestnuts so.

NK: I will say like full transparency. I'm not asking like any like, even though I'm saying politically ecologies, I’m not asking any like political questions. I'm just asking for your your beliefs. I think some people think I'm getting into politics, but I'm just really looking at the emotional feeling and changes and connection to chestnut.

SF: Yeah, okay.

NK: So I would love to hear like first like, your like background of like, where you grew up. And how you ended up to where you are trying to right now?

SF: Yeah, sure. And it's, it's about to start pouring. So I hope this doesn't hurt your audio or your ability to hear me.

NK: No, I can hear you. It's totally fine. No worries.

SF: All right.

SF: So I grew up in Southern West Virginia in a town called Hanton, West Virginia, and spent the first 18 years of my life there. Spent a lot of time hiking, playing in creeks. My papa, I told you this in the email, my papa owned farm in, between Hanton and Beckley in Summers County. We still have a that as a family farm. And my earliest chestnut memory, I have two, you know, probably late, probably 10, 11, 12, I remember my granny collecting Chinese chestnuts from trees from up on the farm, out at the farm, but most of the farm and also at a camp that we have along the New River.

SF: So my papa had planted Chinese chestnuts as part of the West Virginia Department of Agriculture's attempts to replace the American Chestnut. Now, I didn't know anything about the American Chestnut at that time, I just don't have now in retrospect know that, that's why I had those Chinese chestnuts on as farm and why he planting them out at camp those those trees are still there.

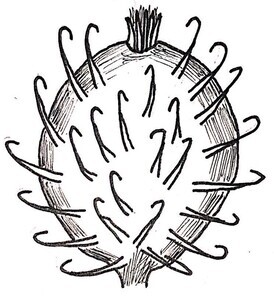

SF: But granny would collect those Chinese chestnuts and I remember hearing crunchy from a bowl of chestnuts on the counter, which were weevils eating the nuts, and I will never forget that sound. And I'm like, Granny, why would you? Why would you eat that and she would just say ‘I just cut it away’ you know, she cuts away all the bad parts and throws the worms away and you just eat the chestnuts you know, regardless.

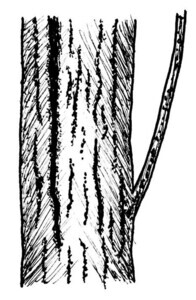

SF: And that's one of my earliest memories of chestnuts themselves. And then my papa, who was a product of the Depression, he hoarded everything. And including, so he taught in one room schoolhouses and Summers County, before he became a superintendent of schools for the county later in his career. But through the 30s and 40s, he taught in one room schoolhouses. He wrote a book actually on the history of one room schoolhouses in Summers County. But as they were starting to tear down those old one room schoolhouses in the 80s 90s, and well, 80s and 90s. He died early in the 1000s. He would collect all the wood but primarily the chestnut that made up those one room schoolhouses.

SF: And the house that I grew up in the basement was paneled. And some of that wormy chestnut that papa had salvaged from those old one room school houses. So I knew that as a story from him, it was a big part of his life. And he passed away before I could really sort of interrogate even more about his connection with the tree. I just knew that he, he had a big connection to it because of his farming upbringing, upbringing, and was really concerned about it. He loved the work that I was doing. His my work only overlapped about two years with him before he died. I just remember him being really excited and hoping that I would plant trees up on the farm when we got blight resistant trees. And that's, that's still my intention. My uncle Charlie still has that farm and we go up there regularly. So at some point in the near future, I want to plant you know, a nice little grove up there and his honor and for the family.

NK: Oh, that's amazing. Do you know which of the restored chestnut that you want to plant? Do you want to do like the transgenomic one or the backcross breed one?

SF: Well, because I'm doing both.

NK: Okay, gotcha, gotcha.

SF: And I have a direct line to get whatever material I want. Then I know my intention is, so the person who is in the car with me, he and I work at Penn State for the Chestnut Foundation and last year was the first year that we put transgenic pollen on our best backcross trees at the arboretum at Penn State. So we've got what's called stack resistance. We're going to test them this summer through a small stem assay and see if that if there really is increased resistance by adding the backcross in with the transgenic tree.

SF: I have strong excuse me strong hope that that will that will be even better than the transgenic on its own or the backcross trees on its own. So that's ultimately what I'd like to plant it down there is stuff that we ended up making and that turns out really good. You know, we have some really good backcross trees. If if the transgenic doesn't get deregulated, and I'm more than happy to plant, you know, the backcross stuff that we've been making, we have some really nice selections that I, I wouldn't mind playing down there at all.

NK: Gotcha. One of the questions I've been asking people is, to what extent do you want to see people planting the restored chestnut? As in on a very small scale in their front yards, or do you want? Would you like to see personally, people going out into the forest and planting it and restoring it? Or where do you fall on?

SF: All of it, all of it. Uh, you know, my previous title, I was recently promoted and given a new title, but my previous title was director of restoration. And even in my new role, I still think about restoration a lot to think about, how's this gonna get back out in the woods? And people say, Sara, what should we play in the gaps? Should we plan just to your question, like small little plantings and backyards or planting big plantings of 1000 trees? Should they be monoculture. Should they be interplanted with oaks? Should they be planted on strip mine lands or replanted in old fields? Or should you, you know, take a terrible site that's like covered in low value timber and strip it and, and put on Chestnut? And I say, yes, all of that. Because the reintroduction of a species across millions of acres is going to take all of that to happen. It's going to take decades, it's going to take millions 10s of millions to hundreds of millions of trees. And you can't do that by by being picky. You know. So really, it's going to take everybody employing every method that they can to get as many trees out there. And I mean, I think what you're talking about priority is going to be well, we're staff priority is going to be and I think that that's a difference.

SF: But you know, people and what they're going to do, I want them to do all of it. Because it really is going to take everybody getting everything they can to get these things out in the landscape on a landscape scale.

NK: Have you been have you personally been met with resistance from people about the hybridity or the kind of just I was talking to Rex Mann, and he was saying the phrase playing God is what some people have said, but have you personally been met with any resistance similar to that?

SF: Yeah, on both ends, so people, people don't like Chinese chestnuts involved in their American chestnuts. There's this sort of inaccurate sense of, of purity of species like I, while I agree that we should have a native tree as native as possible, there's a lot of ecological reasons for that. I'm not against hybridizing, as long as you can keep the ecosystem services that a given species can impart. So I'm not a purist. But but there are people out there who are absolute purists like I want nothing but a pure American, just not. And so they don't want any Chinese in it.

SF: The real high level purists don't even want to a trans gene in it. And then of course, you have the folks who are very anti GMO. And, and all of them have their reasons I don't personally agree with them. You know, my my goal, my philosophy is, as long as what I want is a tree that restores ecosystem and economic services that the species once did and whatever does that let's let's do it.

NK: Gotcha. When you were talking about the first memories of like chestnut, what was, was there any like stories that your father your grandfather, your grandmother mother told you about like the chestnut when it was it? It's like heyday per se?

SF: Unfortunately, no, no, we never. That was never something that we really talked about. I do remember when I so after I've been working couple years, my papa had already passed. My granny was deep into dementia. Going back home and talking to some other local folks who have since passed away too. But it is interesting once you start talking to people, especially in it where I think, I think it was like deep Appalachia like southwestern Virginia, western North Carolina, eastern Kentucky, Southern West Virginia, like people have really deep connections or had deep connections to the tree and the land and the American Chestnut in particular.

SF: So I would hear a lot of the stories on echoed, like being able to take five gallon buckets and just fill them with one scoop, you know, at a time when when the chestnut was at a its height or people let you know the livestock loose into the woods, and feeding the like I had read all of that. And some of the historical literature. And some of the people, the old timers I talked to would echo those same stories, you know, none of which I recorded or documented, but it was just interesting to hear them from firsthand accounts. The person who is so unfortunately, not my papa or granny, or even my, my own father, who's not very outdoorsy.

SF: He did a really full accounting of, and I'll ask him tomorrow, and you're still doing interviews. He got some really great first person accounts of people who are alive and when the blight hit Indiana, which was a little later than like West Virginia or Kentucky, and the way that they sustained their livelihoods was because of the the loss of chestnut. And that was a really interesting perspective that I had not heard. Indiana is the only place where I've heard it where, because the chestnut was dying, people were able to subsist economically very hard times, because they were able to sell the wood, or sell the nuts, as that species was was starting to get wiped out.

NK: I hadn't come across that in the literature anywhere. That's really interesting. And I think like, I share the sentiments you do, like I've heard, I've heard these, like, firsthand accounts. And I think that's like, what kicked me off wanting to do these interviews is because of.

SF: Yeah.

NK: Just like how profound it was. I guess, like that leads to like, another question I've been asking people was like, Why do you care about it? Kind of at a very, like, elementary level of like, what is driving your passion and care for the chestnut? If that's what you do have?

SF: Yeah, I think I do, mine is the people. I mean, of course, I care about the ecology and the tree itself. And I really enjoy the work that I do like working with tree. There's something very charismatic about it, and I can't explain it other than like, it's a beautiful leaf, like it's very aesthetically pleasing, it grows really fast. It's a fighter, you know, just for this thing to hang on for so long after so many assaults. And just keep going. It just it wants to be rescued. You know, and, but the thing that drives me day to day and like gives me energy are the other people who feel the same way.

SF: It's a really amazing community. And I love the people that I work with and share. Like, I'm so, Troy and I are going out to Indiana, we're staying with the Indiana President, Glen Cotinick, he's he's cooking us a delicious dinner tonight. Traveling around Indiana with us meeting other people who are like is growing just nuts with the Savannah Institute up in Wisconsin, and we're gonna see this amazing, naturally regenerating stand up in Wisconsin. I mean, it's just like the stories of people like all their work intersecting. It's not it isn't just one person or one lab or one group. It's just all these people with all these different types of work and approaches and strategies. And we all have to work together to bring the species back. That's that's what I find really inspiring and energizing.

NK: And this is like going into like, your professional career a lot has it.

SF: I mean, that's, that's what I do. I've been working on a single species woman I've been working on just on since I did my masters work on it in 2000, and hired on full time in 2003. And that's all I've done for basically my entire career with the exception of a small amount of time working for a beer magazine and working at Kroger. I've worked on Chestnut not my entire career.

NK: Gotcha, yeah.

NK: I think that's like really different than a lot of the people I've talked to a lot of them are retired or they're up and coming young. But that's really awesome to hear that, has did the like chestnut like changed your perception of the outdoors, or Appalachian?

SF: I tell you what, it's probably not Chestnut specifically, but because the species that I've worked on about tree breeding has made me much more patient. Because it just requires time requires time to grow trees to make trees it takes them a long time to flower and I mean there are techniques to reduce the amount of time for all of those things but it's still a lot easier or a lot harder to work with and say Arabidopsis or tomatoes or corn, you know, and so tree breeding in general has taught me a lot of patience.

SF: I can't go into the woods without looking for chestnuts. And that's when I first moved to State College to Penn State started working there, I joined the caving club. And one of the main reasons that I that I went to cave was because I could rest there in a in a sort of outdoor activity, not outdoors, but you know what I mean? Like not because there's no chestnuts underground. So I wasn't, I didn't feel like I was at work. And I've made peace with that though. I've made peace. And if I'm out hiking, like I know, I'm gonna look for trees. I can I can do that without feeling any anxiety or feeling like I have to document every tree that I find.

SF: It's every now and then it's like, oh, I got to something to get that. Gotta get that tree. I got to stop. Oh, look at that tree, you know? Yeah, every little bit. I’ll still stop and get that I think that's the major thing is that, like, I'm just always looking for them. And just trying to, when I look at the woods. I'm like, you know, what's the eco type is this? Is this going to be appropriate for chesnut planting? Like, what does this mean for restoration in general? Like? Yeah, that's, I definitely have a new perspective. Because of what I do.

NK: Yeah. I feel that with, like, studying botany and like, kind of the green curtain being pulled out from my eyes.

SF: Yeah.

NK: Like always ID’ing the plants. What caused you to have that like transition between? Like feeling anxious if that's correct to like, coming to peace with it? You said?

SF: I think it's just because you you reach a point where do you know, you you there, you have no other choice. You can't control that, right. I mean, and I love like being I love being out in the woods. I love camping. Like I can either be anxious all the time and say that it sucks, or I can just embrace it and deal with it. And you know, that's what some time and some maturity and realizing that, especially like, around where I live, there's Chestnuts all over the place.

SF: Walking my daughter to school up the hill. There's at least 500 chestnuts on that little hill. And I haven't documented them. Yes, I could. And I'm like, oh, I should get up there one day and, you know, document them, measure them and put them a tree snap or like map them. You know, I'm okay that I haven't done that. I think maybe I will one day, like if I lived much more on the outskirts where they are much more rare. Like when I come out here to Indiana, it's a lot harder to find them. And that's, that's a place and a time when I feel much more driven to document anything that I find I look more consciously for trees. But where I live, luckily, they're they're a dime a dozen. I can, I can give it up.

NK: I've asked people to like kind of give their own list of like the plant species and habitat is like perfect Chestnut, in their opinion. So what would you describe like the perfect chestnut habitat? Where you see it, where you kind of see it occur? And what other plant species or like soil types or elevation? Do you find that the most?

SF: It's not fair, I guess, because I've done a lot of habitat modeling.

NK: Yeah, yeah.

SF: So well drained, sandy soils. I mean, what's really interesting is seeing trees and like, for example, Sandy Hook, New Jersey, or in Michigan, or even actually behind my house and what's called the Scotia Barrens, where I see tons of trees, you bend over and you pull up the soil, and it's just almost pure sands. And so, based on our habitat modeling, you know, that sand limit, there's a lower limit, so they don't like any less than 25% sand. And there's actually an upper limit, they don't like any more than 75% sand at that point, there's not enough water holding capacity, and they can't survive.

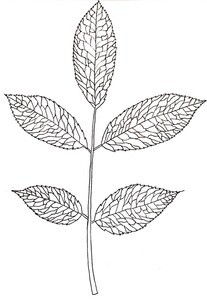

SF: And we see that in defined areas. For example, in southern New Jersey, it's just too Sandy there. But low pH well drained sandy, other species that tend to be much more inclined White Pine, Blueberry, your ericaceous species Azalea, Mountain Laurel, Rhododendron, Chestnut Oak, Hemlock, in some cases. Yeah those are the most often ones that I see in parallel.

NK: Gotcha. Yeah. That's it's very similar to what a lot of people told me.

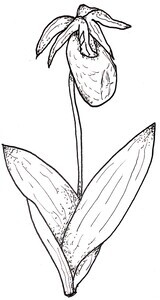

SF: I will say, it's one of the one of the most lovely times to go hiking is sure about now or like a week or two before now when you go out and you see all the spring ephemerals and you see like all, the pink lady slippers and trout lilies and things coming out and similar types of areas, but those aren't as noticeable year round.

NK: I don't know if you've seen this, I just saw it the other day but I saw chestnut it's almost dead because of the blight, but it's like a maybe like four or five inches in diameter. But it had a buffalo nut sapling growing next to it.

SF: Oh really! Okay.

NK: Which I'd never seen growing with, but I because they're like hemi-parasitic. I thought about like, how it could be parasitizing off the Chestnut sapling.

SF: Yeah!

NK: Which was super funny.

SF: Double parasite.

NK: Yeah

NK: I felt bad for the Chestnut. And I was like, it's already, like going through a lot, you know.

SF: Right.

NK: So another question I have is, would you like say that, like, Chestnut became more a part of your identity? Or has it always been a part of your identity? Or how's that, like, potentially become if it's not a part of your identity? What is it a part of a part of your life?

SF: I mean it wasn't always, I would say it went from music and outdoors to I mean, I've always had a love of the outdoors. And then I started following what I've, I've always loved Duke basketball. Then I went to Duke and I became an absolutely rabid fan of Duke basketball. And then, you know, I started my career. And then I had kids. And so now it's funny you go through my phone and what I have pictures off it's like Kid kid tree tree tree kid kid tree tree kid tree. And that's like all it is. So that's that's kind of where I'm at right now in my life.

SF: Do your, do your kids have a passion for the chestnut or?

SF: Um, kind of, I mean, they still so they're young. They're five and seven. So they still don't hate it entirely when I take them to the greenhouse. Come on, kids, let's go water the trees you're like, okay, because they can run around. And Parker, my daughter is actually in the last magazine with the chestnut magazine. She came up on a trip with me to Erie, Pennsylvania. And so there's a picture of her and one of the LSAs near Erie. And actually, this past week, they went with me to New York, and we dropped off a bunch of trees and they love going to New York because they love New York Park hot dogs. So I'm like, Come on kids. Let's go, you know, do do these dog and ponies. And I'll get your dog in New York and like, okay, so I don't know if it's so much they love the tree. They just kind of like hanging out with mom. And I'm sure one day that'll change. But for now, it's that they're okay with it.

NK: Gotcha. Um, did you have any other pieces of Chestnut growing up? Or do you have like Chesnut in your house? Kind of as a product that you use or?

SF: Yeah, so because, well I have a lot of that wormy chestnut from from my house, my childhood home, we sold and moved into another home in town that was that we inherited. And before we moved, my dad pulled all the wormy chestnut from the basement. And we took that with us. So I still have some boards from the house.

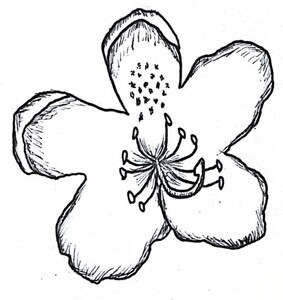

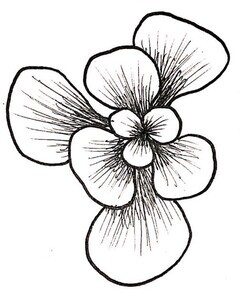

SF: Oh, that was a big ol rock that I don't think broke our windshield will say good thing. Good thing. It's a rental. So, so I still have a couple of those boards with the wormy chestnut that my papa had taken out from from the one room schoolhouses. That was in our basement. One of our members actually wasn't a member. He's a he was a woodworker in West Virginia. He then made a really, really nice walking stick out of some of those boards. That turned out great. And then when I got married to my husband, people showered us with lots of Chestnut stuff's rather beautiful, Chestnut table. I've got Chestnut bowls, I've got Chestnut frames. There was actually a really nice set of postal stamps that came out about 10 or 12 years ago, got feature chest on as part of like the Eastern Appalachian woody ecosystem, and there's a blighted cesta in front of that scene. And so my dad got a bunch of those and then had him framed and wormy chestnut frames. And so that's hanging up in the house. I got a whole bunch of chestnut stuff in my office, of course. So Oh, and a friend of mine got me like a set of glasses that have etched chestnut flowers and leaves on them. So yeah, it features not as prominently as or it features a little more prominently than I would like but I mean, what are you going to do? I got just the earrings I got I got all kinds of stuff.

NK: Do you have a favorite piece?

SF: You know, it's really hard to choose now that you're asking. I think the most sentimental would be my my father's passed away too. So I would say you know that frame and Chestnut stamp just because you know, that was something that he put together and he was very proud of the work that I do. I love the walking stick because it looks really cool. And it was made by an awesome woodworker in West Virginia. The table is beautifully made. It's a really spectacular piece. So you know, each one of them have a great story that means a lot to me. But yeah, probably the framed stamps because it's from my dad.

NK: Thank you for sharing that. That's really awesome. What one of the questions I have, and this is like, kind of, I haven't been able to find in the literature, and I was wondering if you know, do you know how long the roots can live and produce the stump or the little saplings out of, and like how long?

SF: I don’t, we don't know that. So from what I understand the root systems as long as they can be released over and over again, and they get enough sunlight, and the deer don't eat them all to hack, or they don't get made it to a Home Depot, like as happens in some places. That's true story. Then, then they can persist indefinitely, from what I understand. As long as they can get released and throw up new sprouts. Whenever they throw up the sprouts. They create new root systems that that can then that are no no longer exhausted. So like the old root systems are probably long gone, what they've done is created new roots on top of those old ones. But if those suppressed sprouts don't have access to enough sunlight, or the deer keep eating them back they're not regrowing more robust root systems, and then they get exhausted. So I think the answer is more resource-related than time.

NK: Okay, gotcha. I've been like people have asked me and I like, have no clue what to say. I say, I don't think anybody really knows. Because we haven't had enough time to figure that out. But yeah,

SF: I think I think it's resource limited.