Savannah Clark Interview Item Info

Topics:

Nick Koenig (NK):I'll I told you about the project first, I was in the, I'm gonna be transparent in this. So in our study, we're just looking at questions of human environment relations. And they were like, just like started digging, tell a story that hasn't been told. Try to tell it with people. And I was like, okay. Oh my god, like, everybody talks about extinction. But nobody talks about plant extinction, or like the lesser majority.

Savannah Clark (SC):Yeah.

NK:And I was like, Okay, I want to, I want to learn more about this. So then, I've been interviewing people who are Appalachian or grew up in Appalachia and then who have some ties to the Chestnut whether that be from childhood, whether that be from recent years. Talk to people everywhere in between.

SC:Have you got a lot of stories from people that like...

NK:Old timers?

SC:Old timers

NK:Yeah.

SC:Oh, so cool what they remember of the Chestnuts

NK:So feel free to just tell me what you want to tell. Don't tell me stuff that you think I want to hear. Just tell me exactly what you feel or what you don't feel about it. But the first few questions are just like, like a background where you grew up and where you're from?

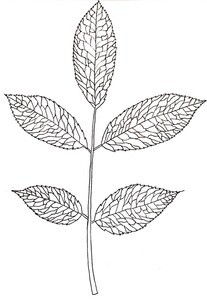

SC:Well, I grew up in Bath County, Kentucky, which is kind of like in the foothills of Appalachia, really close to Cave Run Lake and a lot of the community there is super like it's just, they love to forest, everyone it's that's part of the community in Bath County is like getting out and going to forest, going hunting, having a good time and enjoying it. But I feel like a lot of the community doesn't realize the, the conservation effort and stuff that goes into it. And that's what really drove me to go into conservation work and start like, helping out with the forests and stuff. And like, because I wanted to spread that knowledge and Bath County in general, I don't know about Chestnuts there, like I don't have I have never dug deep into like the history of Chestnuts in Bath County, but I'm sure they were there.

Just a lot. Yeah. Foothills of Appalachia, a lot of country, a lot of us are country, you know, old timers have those big stories. And...

NK:I know like, imagine, I don't know you, you know

SC:Okay,

NK:Because I know some of the stories you've told me, you know, act like you never told them to me, but what did you do, like growing up? Like day to day, if you were outside of school?

SC:So, I guess. Yeah. So like, let's, let's say this summer. So I'm, in the summers, it was a lot of times I spent my time, most of my days with my nanny and my papaw at their farm back in Sharpsburg. And they, we were always just going outside and playing ,me and my brother having a good time. And they had this little plot of forest that was like right back on the corner of their property. And we always go back there, climb the trees, and just kind of explore around and see what we could find.

And it was just so like, great to be in the forest and like getting away from everything. So the forest was super, such a, such a special place and it all like inspired that curiosity in me because I wanted to find out like where, like what everything was and like what it did, and like how it played into the ecosystem. And it was just so, so fun getting to go out in the forest and learn about all that stuff.

NK:Did you know you wanted to study bio in high school?

SC:No. In high school I wanted to, I wanted be a doctor.

NK:Oh really.

SC:I wanted to go and be a dermatologist. And, but that time I was more, I was very, like, I don't like saying it. But I was very money hungry, at that time. I was like, Yeah, I want to get a good paying job that I can take care of myself and my entire family. But then I slowly realized, like through college like I would be miserable doing that. So I want to do something that I actually enjoy. And that's what really like when I took my first botany course, that brought me back to that curiosity that I had as a child.

And I was like, this is it. Like I want to go into forestry and like botany and studying management and ecology now and figuring all that, figuring out those questions out that I had as a child and like actually learning in depth answers to them. So that's what drove me into forestry.

NK:Did you learn about the Chestnuts in the botany class?

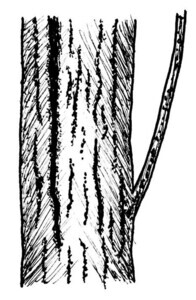

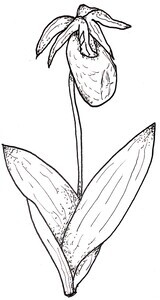

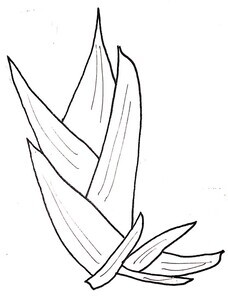

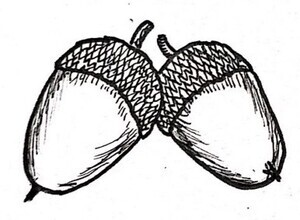

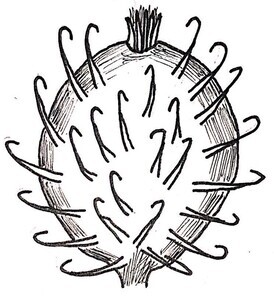

SC:So yeah, that was the first time like I actually truly learn about like what happened to the American chestnuts. Because it wasn't like, I talked about in community, like there, everyone had Chestnut, pieces of Chestnut furniture that were like super valuable. And all this. I never really knew why they were valuable until I found out about the blight and like the extinction of the chestnut.

And through that, like once I started learning about the Chestnut, I was like, Oh, I really want to work like, work with this some. And that's when I started working with the American Chestnut Foundation, out of the orchards and stuff. During their workdays, I got to help them out with the Kentucky State Fair, doing like just a little info booth with them. And that was so fun.

NK:What did you do there?

SC:So they had like a little Plinko game setup. Yeah, with Chestnuts and they would drop them and drop them in and they get a prize of it when in the right thing. And like, I was just kind of like informing everyone just like, Hey, do you know that we used to have like trees as big as the Redwoods in the East Coast. And like, we can have that again. And just trying to get kids excited to learn about Chestnuts that was like my thing there.

Nk:Why? Why did you want to get kids excited?

SC:Because kids, they're the next generation. They're the ones that are going to carry on our efforts that we can like that we are working on now. Like, if we don't inspire that curiosity and love of nature and stewardship in them, then we're not gonna, then all of our work now is pointless. So if we don't, we gotta like, it's on the next generation to continue this on. So it's has to have to have to have them inspired.

NK:You said furniture was Chesnut, do you have some here?

SC:So I don't have any of my apartment. But I have a piece that my nanny gave to me from my grandma Clark. She got it from her father. Yeah, her father, trying to remember the story that, her father got it from a carpenter that lived over in Brown County. And he she bought it for I think was like 10 bucks at the time. And then my nanny, she actually put it out in a yard sale one year and was trying to sell it for like 400, 500 bucks, because it was Chestnut.

No, no one, no one in Bath County had the money to spend on $400, $500 on it. a chestnut wardrobe, so she just passed it down to me. And like, I'm so grateful that she kept it because it's just so so beautiful. And like, such a it's like a piece of history too, because it's got all that, that that wood from those trees. And it's kind of inspiring, like we could have this, like not necessarily the furniture, well, we could have like the wood and bring back that culture that went around the American Chestnut, if we brought the chestnuts back

Because I mean, Chestnut hunting, and then the chestnut logging, like, it was all such a huge important part of the community and the culture of Appalachia. And then now it's just gone. And I feel like bringing it back would be like a collective, I don't know, it would be good for the collective and like bringing everyone together and bringing back some of that tradition because I feel like Appalachia has a loss a lot of that, like, we've kind of become separated from each other in a way but I feel like the Chestnut could bring could bring some people together. Obviously, it's not gonna bring everyone together. Bring a lot of people together, especially like in the woodworking communities and people collecting chestnuts to roast and all that stuff.

NK:Have you ever eaten a Chestnut?

SC:No, I actually haven't. I've had like, I've tried like a Chinese chestnut, but never a true American chestnut.

NK:Bu you have eaten a Chinese Chestnut

SC:Yeah.

NK:I've never, I've never eaten them.

SC:They're, they're good. It's like soft and crunchy at the same time. I don't know how to describe it. Like when they're roasted. It's so good. And nutty.

NK:I think you'd be able to get some from saplings

SC:Yeah, that's what I was telling my mom. I was like, Yeah, you guys like I'll go out there and do the hand pollinating for you guys. And you guys can collect them and we can roast them for Christmas.

NK:What do you think is like a part of like an Appalachian identity, kind of those core values to you?

SC:The core values of Appalachia? Family. That is number one, I think family above, is above everything else in Appalachia, because without that strong family bond, you're not going to survive in a lot of these areas like you have to have that connection and like there's people around you to help get you going and also family like that's, that's your roots right there.

And that's what shapes you and develops you into the human you are and Appalachia it's a family. Community to a sense, because, there's a if you go through a lot of like Eastern Kentucky towns, they're gonna have like fish fries, like someone's house burns down, they're gonna put it there. The whole community is going to come together to support that person and make sure that they have what they need.

NK:Did that happen to anyone you knew growing up?

SC:Yeah, so, one of my best friends in high school, her name CD, and she, her house burned down. And we everyone came together for whole high school and we did a fundraiser for her to get, help them find a new place. Get her. It was so great. We like everyone collectively in the high school got her a bunch of art supplies, but she was an artist and helped her get her like she was able to save a couple of her paintings. And it's so amazing because like she is gone so far in her art now and it's like the community didn't come together to support her and get her back on her feet. Like who knows where she would be like she is doing big things in the world right now.

NK:Do you remember when you first ever like heard of Chestnut? The first encounter?

SC:It was probably like talking about like, like furniture and stuff earlier as like when I was a kid I never really like truly understood like how big and massive and important these trees were until I got into college.

NK:What type of furniture was it?

SC:So I had a, I have a wardrobe.

NK:The Chestnut wardrobe.

SC:And then my nanny's also got no she sold it, but it was a coffee table that was made out of Chestnut. And then I think that's all the pieces of furniture that she had. And then my mamaw, my mamaw, Annie, she's got a dresser just like a normal dresser. I'm trying to think if anyone else I know, furniture. That's all I can think of right now.

NK:Did you did, have you ever talked to any old timers about Chestnut about when they used to see the chestnut trees or anything?

SC:So no, but like, that is something I want to do. Like I want to get back and like back into community in my community and Bath county now a lot more involved in it. And learning about how, like what Bath county looked like before it was really developed. Because throughout my life so much of the county has been expanded into and like, like we used to have like right off of the exit there used to be a big forest like right, not like a big forest, but you know, like secondary succession, that kind of area.

And they just cut it all down to build a trailer park and a Save-A-Lot. And I'm like, Yeah, I guess we needed the housing and stuff. But there's so many areas that were already cut and like big fields and like old farmland that we could just reuse and repurpose into something else but...

NK:What kind of like feelings does the Chestnut give you? That's kind of a broad question. When you've worked with the Chestnut?

SC:Hm, I'm trying to think of how to describe it.

NK:Like when you're working out at the orchard or kind of the encounters maybe with the furniture?

SC:Hopeful honestly, because it's really hopeful, inspired. Because seeing all these people work together so hard on, just for just this one tree, this one species of tree. And if we could take that collective effort like that collective effort to for one to reimagine what would you do for everything? And like for the whole forest, and it's just getting that attitude expanded I think. Hopeful inspired.

NK:Why should ,Why do you care about the Chestnut? Or why do you, why do you spend time with it and volunteer?

SC:I mean, I love trees. That's first and foremost. I just love trees, like there's something, something about them that just brings me so much joy and like I just look at a tree and I'm like, this is what allowed us to come up and like did like, allowed us humans to evolve and like just to get here but without. They just filled me with joy. Honestly, every time I look at a tree, I'm just like, Yes, this is, this is what I'm meant to be doing meant to be protecting.

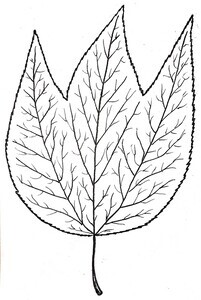

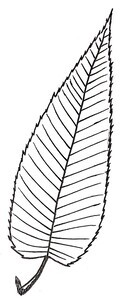

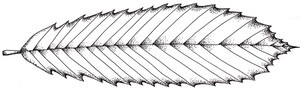

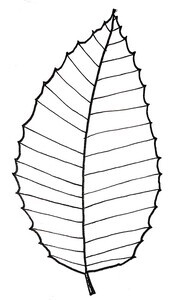

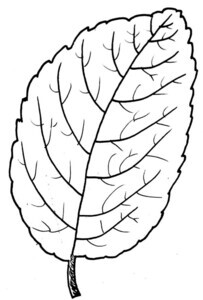

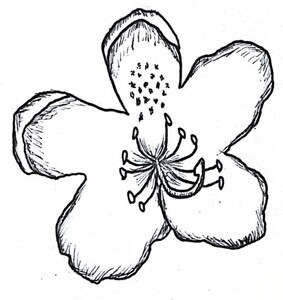

And the Chestnut it's super. I care about it because like imagine, just imagine like we had these massive trees out here like the redwoods because I've seen them and like and it was so ecologically important, like, Isn't one in every three trees previously was American Chestnut like to have that out here, again, these massive beautiful forests that have this incredible canopy that could support an entire different level of life that we had.

And I don't know just having that, that diversity, magicalness back in the forest would be so so beautiful, amazing, I just, every, all the good stuff, it would be so great.

And like I said, I think having the Chestnuts back to would help kind of bring a little bit of a sense of community back as well, because like so many people can like, think that to cut down one chestnut tree, that you can't do that with one person. Like, it's going to take a multiple, it's going to take a whole group of people to bring that tree down.

And then the people that have to work with the wood and then build it into something and then people coming out and collecting Chestnuts as a family before Christmas to roast them. And they just it's just a lot like community, beauty, inspiration, yeah.

NK:So in terms of like the restoration efforts, what extent do you think it should be restored? Or should it be restored? Or how would you like to see it restored in Appalachia? Yeah, how would you like to be see it restored in Appalachia? If, if you want to see it restored?

SC:Well, I definitely want to see it restored in Appalachia, how though? I feel like incrementally doing it, like saying, because right now we're at a point where we don't have Chestnuts that are completely blight resistant. So getting those into areas and finding out like which ones which areas it's going to be, like, thrive in the most while it's in these early stages. And then moving on to wider areas and actually, and like letting the Chestnut spread itself.

And like not really forcing the reintroduce it and reintroduction to it but like going in maybe to our public lands, starting there and introducing it and then slowly having like community programs, where we could be like, Hey, we have this, like we have Chestnuts here that we can give you and help you like reintroduce them onto your land. And here's the benefits of all the chestnuts and like getting people slowly to kind of introduce those on farmlands and the places that they were before.

NK:Do you have any like, thoughts on on, do you have thoughts on either the hybrid or the transgenomic one specifically?

SC:So the hybrid one is the one they are actually cross pollinating.

NK:Yeah

SC:Okay.

NK:And then transgenomic one is the gene.

SC:They're actually going in selecting the blight resistant gene and entering it?

NK:If you don't have any thoughts on it, then...

SC:I yeah, I don't have an opinion on that one. Because I haven't looked that deep into like the difference in those efforts, in the efforts. I just know that. I mean, whichever one I think makes the most like, gives the tree the Blight resistance but keeps the most of the genetic integrity of the actual American chestnut. Because I feel like once you get to a certain point with crossing them, we're going to have a whole new species. And so technically wouldn't be an American chestnut. But then again, species identification, that's just that's, that's just that's a human thing that we've, we've come up with, but because every, every plant is going to have some genetic, genetic difference. It's just finding when is that genetic difference to go into a new species?

NK:Would you plant Chestnuts on your property, if you could?

SC:Oh, hell yeah, I mean, um, of course, I've got the ones in the office. I've called, I called my nanny, I was like nanny, can I put a chestnut in your yard? She's like, Yep, I was like Mom can I put a Chesntut in your yard? She was like, Yep. And I like, Dad, Chesnut in your yard? And he was like okay. And like everywhere, Chestnuts everywhere I can plant them and spread them as far as I can. I really hope that I can get on that land, the 30 acres that we have back there so that I can plan a bunch out there.

NK:Do you have anything else you'd like to add? Chestnut stories, storytelling. Anything in general

SC:I don't think I have any stories. I mean, whenever I was at the State Fair doing that work, the American Chestnut Foundation, it was just, the wonder on kids faces when you're like, we could have trees as big as like, huge trees, as big as redwoods out here. And they're just wow. Like, we really had those one time. And I'm like, Yeah, we could have them again. And just, I think that emphasis on informing the next generation and getting them inspired to continue the efforts and realize that we can have these back. It's potential, like if we if we just continue working on it. Like that's, that's my driving, drive drive home point.

NK:Okay, I have one follow up question to that.

SC:Okay.

NK:When you say informing next generation, is there a reason that you so deeply emphasized, next generation? Is it a tie to the future or tie to the forest or a tie to religion or to the youth?

SC:It's a tie to prosperity, I would say, because, like I said before, kind of all of our work now is pointless. If we don't continue like continue , make sure that next generation has that information to continue our work, and continue the stewardship of the forest.

NK:Thank you, Savannah.

SC:Yes.

- Title:

- Savannah Clark Interview

- Creator:

- Koenig, Nick

- Date Created:

- 2022

- Description:

- Interview with Savannah Clark

- Location:

- Eastern Kentucky University

- Latitude:

- 37.73823073

- Longitude:

- -84.29690252

- Type:

- record

- Format:

- compound_object

- Preferred Citation:

- "Savannah Clark Interview", Chestnut Collective, Nick Koenig

- Reference Link:

- /chestnutcollective/items/chestnut050.html