Haunting ghosts

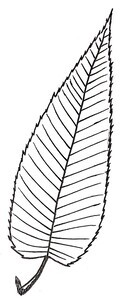

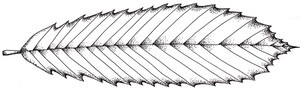

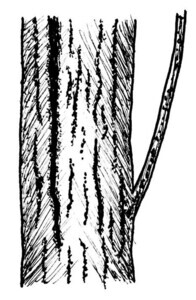

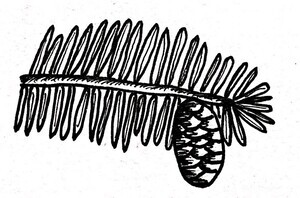

Very often, the forest ecosystems where the Chestnuts used to reside and currently reside were covered in what has become to be known as ‘grey ghosts.’ The ‘grey ghosts’ are the American Chestnuts trees that have died due to the Blight’s infection but were not salvaged/harvested by corporations or individuals to harvest the timber (Figures 23 and 24).

Therefore, the trees were left standing for years after to slowly be consumed back into the forest ecosystem by insects and fungi, as well as served as places of shelter for a myriad of life forms. Chestnut trees are noted for being prone to rot and this rot-resistance allowed the trees to stand for longer than other species of trees. For Rex, when asked of his first encounter with the American Chestnut, he said:

“I remember as a child, going into the woods with my dad, and the old, we called them grey ghosts. The old chunks of the Chestnut, the stumps were everywhere.”

Rex, Wednesday June 28, 2023

The emotions evoked by Appalachians when discussing the grey ghosts is made up of a suite of feelings regarding the standing trees. Interestingly, the grey ghosts also serve as physical pieces of the emotional political ecology of the salvage economics (Tsing, 2015) and communications that was advertised during the height of the Blight’s spread. Land-owners were encouraged by the government and forest service to harvest all the Chestnuts that stood in the Blight’s path as there were no known ways to combat the fungal infection.

Additionally, in the early stages of the Blight’s infection, the Chestnut wood is still viable for timber production and can be salvaged. The grey ghosts, once they reach a point of non-harvestable wood, were in some sense left in the forests to remind humans of the lost capital that was not gained. The grey ghosts also served as physical markers of where the forest was transitioning to other forests types dominated by different species, Rex and Ken expanded on this point by saying:

“All ghosts were ever you know, the old dead stems, but but they were all dead. And so I spent the early years of my career watching the forest adjust to the loss of that Chestnut, you know, just how the other trees were growing in to take the space where those trees grew.”

Rex, Wednesday June 28, 2023

“And I just remembered as a kid, there was just this long run of dead trees. They were gray and straight up because of course it was forest. So it was straight up so trees are gonna grow up to compete tall and straight. Compared to like now you see bushy trees and orchard that kind of thing. These were competing trees…But there were still big trees at that point, dead trees kind of crumbling and falling apart. Just kind of scattered here and there…I remember as a kid that were still the full size. I mean, they still had the full branches. The tips of the branches leaves of course, were long gone. The bark was long gone. But as you remember, it took years for those trees just to slowly fall apart.”

Ken

Many theorists and researchers delve into ideas of hauntology and ghostly existence in the world and the Anthropocene (Searle 2021). There was a large amount of data and materials in both the archives and interviews regarding ghostly existences and these accounts could provide for the introduction of plant hauntologies and botanical ghosts to the spectral ecologies which are dominated by animal geographies currently (McCorristine and Adams, 2019; Barlow, 2000). From the ghostly imaginaries and ways of existing, we can gleam new insights into the ethics of violence from the Chestnut as well.

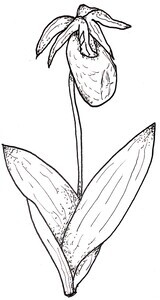

Informed by Yusoff’s (2012) writing on using the lens of violence in analyzing conservation, from ethnographic work, there was an underlying presence of violence that was deployed by the community members engaging in the volunteer work through the American Chestnut Foundation. Rather than seeing this as simply negative, an ethics of violence has been used by the foundation for the end goal of restoring the species. Often evoking emotions of guilt, disgust, and sadness, when seeing violence, types of violence are being justified by people and organizations for species proliferation (van Dooren, 2011).

The main types of violence observed are the intentional infection of the hybrid American-Chinese Chestnut saplings with the Chestnut Blight for purposes of identifying the blight resistant trees and the subsequent non-Blight-resistant trees (which are later culled/cut). However, after the violent inoculation, killing, and cutting of the trees, the tree’s life could be seen as honoured as being transformed into a walking stick. I was gifted one of these walking sticks from Ken and the American Chestnut Foundation and see it as a haunting and ghostly existence of the tree as well as a reminder of the violence ensued for their goals of restoration.